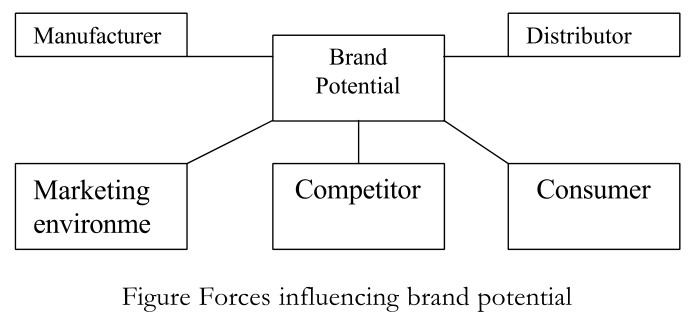

It is not unusual for an organization to be under-utilizing its brand assets through an inability to recognize what is occurring inside the organization. Have realistic, quantified objectives been set for end of the brands, and have they been widely disseminated? Aims such as ‘to be the brand leader’ give some indication of the threshold target, but do little in terms of stretching the use of resource to achieve their full potential. Brand leadership may result before the end of the planning horizon, but this may be because of factors that the organization did not incorporate into their marketing audit. But luck also has habit of working against the player as much as working for the player! Firms such as 3M and Microsoft have shown how brand and corporate culture are closely interlinked and how they affect each other. Their brand mission focusing on innovation is backed up by a corporate culture encouraging experimentation, banning bureaucracy and publicly recognizing success. Since the culture of an organization strongly influences its brands, mergers and acquisitions can alter brand performance dramatically.

Has the organization made full use of its internal auditing to identify what its distinctive brand competences are, and to what extent these match the factors that are critical for brand success? For example, Swatch recognized that amongst fashion- conscious watch owners its distinctive competences of design and production could satisfy changing consumer demands for novelty watches.

Is the organization plagued by a continual desire to cut costs, without fully appreciating why it is following this route? Has the market reached the maturity stage, with the organization’s brand having to compete against competitors’ brand on the basis of matching performance, but at a reduced price? If this is so, all aspects of the organization’s value chain should be geared towards cost minimization (e.g. eliminating production inefficiencies, avoiding marginal customer accounts, having a narrow product mix, working with long production runs, etc.). Alternatively, is the firm’s brand unique in some way that competitors find difficult to emulate and for which the firm can charge a price premium ( e.g. unique source of high quality raw materials, innovative production process, unparalleled customer service training acclaimed advertising, etc.)? Where consumers demand a brand which has clear benefits, the manufacturer should ensure all departments work towards maintaining these benefits and signal this to the market (e.g. by the cleanliness of the lorries, the politeness of the telephones, the promptness of answering a customer enquiry, etc.). In some instances, particularly in services, the brand planning document can overlook a link in the value chain, resulting in some inherent added value being diminished (e.g. an insurance broker selling reputable quality insurance from a shabby office).

Significant cultural differences within several departments of a company can affect the brand success. The firm should not only audit the process to deliver the branded product or service, but also the staff beliefs, values and attitudes to assess whether the firm’s culture is in harmony with the corporate brand identity and whether the firm has the appropriate culture to meet the brand’s mission.

Distributors

The brand strategy of the manufacturer cannot be formulated without regard for the distributor. Both parties rely on each other for their success and even in an era of increasing retailer concentration, not withstanding all the trade press hype, there is still recognition amongst manufacturers and distributors that long-term brand profitability evolves through mutual support.

Manufacturers need to identify retailers’ objectives and align their brands with those retailers whose aims most closely match their own. Furthermore, they should be aware of the strengths and weaknesses of each distributor. Brand manufacturers who have not fully considered the implications of distributors’ longer-term objectives and their strategy to achieve them are deluding themselves about the long-term viability of their own brands.

Working with a distributor, the brand manufacturers should take into account whether the distributor is striving to offer a good value proposition to the consumer (e.g. Kwik Save, Aldi) or a value-added proposition (e.g. high quality names at Harrods). In view of the loss of control once the manufacturer’s brand is in the distributor’s domain, the brand manufacturer must annually evaluate the degree of synergy through each particular route and be prepared to consider changes.

The brand manufacturers must recognize that when developing new brands, distributors have a finite shelf space, and market research must not solely address consumer issues but must also take into account the reaction of the trade. One company found that a pyramid pack design researched well amongst consumers, but on trying to sell this into the trade it failed – due to what the trade saw as ineffective use of shelf space!

Consumers

To consumer, buying is a process of problem solving. They become aware of a problem (e.g. not yet arranged summer holidays), seek information (e.g. go to travel agent and skim brochures), evaluate the information and then make a decision (e.g. select three possible holidays, then try to book one through the travel agent). The extent of this buying process varies according to purchasers’ characteristics, experience and the products being bought. Nonetheless, clearly consumers have to ‘work’ to make a brand selection. The brand selection and brand ‘usage’ are not necessarily performed by the same person. Therefore marketers need to identify all individuals and position the brand to appeal to both users and purchasers. In business to business markets several groups are involved in the purchase decision. Marketers need to formulate brand strategy that communicates the benefits of the brand in a way which is relevant to each group.

Competitors Brands are rarely chosen without being compared against others. Although several brand owners benchmark themselves against competition, it often appears that managers misjudge their key managers should undertake interviews with current and potential consumers to identity those brands that are considered similar. Rather those collecting useless and misleading data managers should undertake interviews with current and potential consumers to identify those brands that are considered similar. Once marketers have selected the critical competitors, they need to assess the objectives and strategies of these companies as well as fully understanding their brand positioning and personalities. It is also essential not to be restricted to a retrospective, defensive position, but to gather enough information to anticipate competitive response and be able to continuously update the strategy for brand protection.

Research has shown that return on investment is related to a product’s share of the market. In other words, products with a bigger market share yield better returns than those with a smaller market share. Organizations with strong brands fare better in gaining market share than those without strong brands. Thus, firms who are brand leaders will become particularly aggressive if they see their position being eroded by other brands. Furthermore, as larger firms are likely to have a range of brands, backed by large resources, it is always possible for them to use one of their brands as a loss leader to under price the smaller competitor, and once the smaller brand falls out of the market, the brand leader can then increase prices.