Television compounds the problems of radio by simultaneously mixing two separate channels: audio and video. Thus, one small part of the television control room is devoted to audio mixing while the major portion is devoted to the mixing of video images. The inputs that the director must monitor are many. There are three different cameras in the studio itself that the director shifts constantly to obtain specific shots of the performers. In addition, there may be remote cameras at other locations, especially for live news coverage. Meantime, video elements of the program may be prerecorded and stored on videotape, film slides, or computer memory. For television news programs, two or more videotape recorders are systematically loaded and the tape cued to present one story after another without pause. There may also be video inputs from one or more film chains; that is, 1V cameras hooked up directly to film and slide projectors. And, most certainly the control room includes one computer that generates caption material and other text and another called a frame storer for graphics and still pictures. The videotape recorders, the live remote cameras, and the film chains add new audio inputs that must also be monitored.

In the end, then, the director must keep all these inputs straight, directing the video switcher -and the audio engineer in the proper selection of inputs to create the desired output. The script, while it does not designate exactly which device to choose for the proper input, does designate the type of device used. The director will decide precisely whether camera no.1, no.2, or no.3 shoots the anchor head and shoulders and whether videotape recorder no. 1 or no.2 plays the mayor’s news conference story. But the script must provide technical cues to identify when the anchor is on camera and what medium was used to record visuals of the mayor’s news conference.

With so much to keep track of, it’s not surprising that the first television production scripts were designed to reflect the simultaneous tracking of video and audio inputs. Rather quickly, however, scripts for fictional television programming adopted a format that reflected their theatrical and cinematic character. However, there are still two readily used split-page script formats: Live-1V and 1V News. We will look at them first because they graphically reflect the interplay between studiond control rooms in television production.

Live-TV

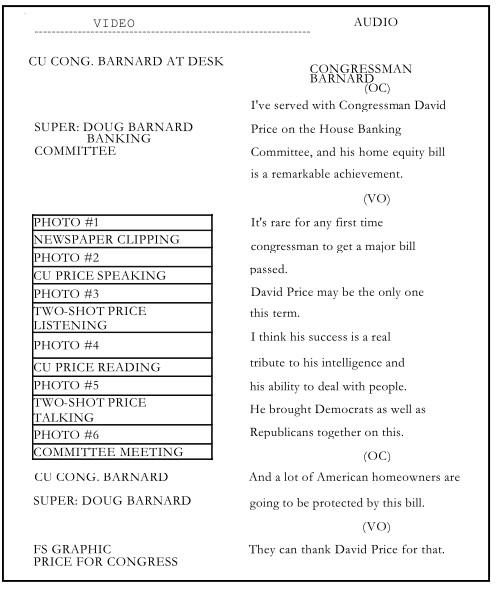

The Live-TV script example that follows on page 30 is for a 30- second political commercial that aired during the 1988 election campaign. The script page is split into video and audio columns, with a vertical line down the page just to the left of center. There are I-inch margins all around and considerable white space to give the director additional room in which to “mark up” the script; that is, to add time cues and notes, designating camera shots, video sources, and verbal instructions for the crew during production. Note also that the spoken parts of the script are typed within an audio column that is 35 characters wide. Each 35-character line takes approximately 2 seconds to read. Thus, even before production begins, we can estimate the time of this spot-30 seconds-by counting lines of copy. Generally, all the partial lines will average out if we count only the ones that extend at least half way. In this case, the lines add up to 15.

Fundamentally, this ad is a testimonial from Congressman Doug Barnard, who sits on the House Banking Committee with Congressman David Price. As we can see from the audio column, Barnard does all the talking. He begins at a desk on camera (OC) and continues voice-over (VO) as the audience sees a montage of still photographs of Rep. Price at work in Washington. With three lines of copy (6 seconds) to go, Barnard reappears on camera momentarily but gives his punchline -ending voice-over while the viewer contemplates a full screen (FS) computer-generated graphic that reads: DAVID PRICE-Everything we ever wanted in a Congressman. (Need- less to say, a lot happens in 30 seconds. In the studio, we have one camera taking a close-up (CU) shot of Rep. Barnard sitting at a desk. In addition, we need two cameras focused on two easels with the photographs arranged for a smooth transition from one to the next. Photos 1, 3, and 5, must be lined up on one easel with a camera focused on it while photos 2, 4, and 6 are lined up on a second easel with its own camera. (Those photos could also be stored digitally in computer memory for recall during production.) The director tells a technician to roll the videotape and then cues Bernard, who starts reading his script off a teleprompter. While Barnard is on camera, his name is superimposed at the bottom of the screen.

Four lines into the spot, the video source changes The director tells the video switcher to dissolve to photo no.1 on the first easel, then to photo no.2 on the second easel, then photo no.3 on the first easel, and so on. (Dissolves are the fading out of one image as another fades in. While dissolves are often used to suggest the passage of time or a major change in the setting, in this 30-second spot they reinforce the thematic flow of the visuals. If direct cuts were used, then the pace of the spot might appear too hectic, given a change in the video almost every 3 seconds.) The spot concludes with a shot of Barnard at the desk again and then the computer-generated graphic as Barnard reads the closing line.

As precise as the Live-TV format seems to be, it should be pointed out that it does not present a perfect schematic for the interlocking elements of this 30-second commercial or any other complex script.

(In the political ad, PHOTO # 1 and PHOTO #3 are indeed matched with the first words of corresponding text. However, the match between PHOTO #2 and the audio copy is much more ambiguous. In the actual commercial, the dissolve occurs on the word “get” in the middle of the line)

Sometimes, in fact, the writer may circle the precise word that corresponds to a change in video and then draw a line back to the video cue. Clearly, though, some leeway is permissible. The writer can reasonably assume that an experienced director will dissolve from photo to photo at an aesthetically pleasing pace.

Another inconsistency in the Live-TV format is the mixing of both audio and video information in a single column. For instance audio column of the political ad includes the OC and VO notations that let Rep. Barnard know exactly when he’s on camera. During the VO portions, he need not worry whether he’s squinting at the teleprompter. He can even look down to read from a written script in front of him. On the other hand, if audio and video channels are recorded simultaneously as on videotape, then information about audio sources is often found in the video column. Accordingly, some professionals like to think about these split-page formats as divided into a left column for technicians and a right column for on-air talent. The director, of course, must coordinate both.

TV News

The production of television newscasts differs from the production of most other programming in one essential way. Much of the newscast is live, unrehearsed, and unedited. When the anchor kicks a line, the audio engineer fails to turn off a microphone, or the video switcher hits a wrong button, the viewer knows it instantaneously. As a result, writers and producers try to minimize the technical complexity of live elements in 1V newscasts. In fact, 1V news scripts are surprisingly simple to decode once you’ve mastered the alphabet soup of technical jargon.

There are, for instance, only a few basic in-studio shots. Anchor on camera (ANCHOR OC) designates a head and shoulders close-up when the anchor is reading a news story directly to the viewers. When a second video element is added to the basic ANCHOR OC shot, it is called a chromakey (CK) shot. Chromakey once referred to a specific technical process for mixing two video pictures electronically. Now it is the generic term for any shot where the camera frames the anchor to one side so that a photo, a graphic, or even rolling videotape can be inserted into a framed portion of the screen. A map inserted over the shoulder of the anchor, for instance, helps identify the story while adding visual interest to the shot. When short news items are run in rapid succession, changes in chromakey graphics mark the transition from one story to the next.

Aside from chromakey shots, the vast majority of technical notations in 1V-News scripts relate to the use of videotape, abbreviated VTR or ENG. ENG, which stands for “electronic news gathering,” refers both to a technology-the lighter, more compact video recording equipment that replaced film in the mid-1970s-and the special cassette tape format it employs. The audience rarely sees or hears raw videotape on the air. Rather, they watch an edited version that a reporter or anchor narrates.

Because reporters like to go home at night for dinner and not return to work for the 11 o’clock newscast, they almost always record their narrations on the edited videotape for playback during the newscast. In the script, these videotape stories are technically identified as VTR/SOT. VTR/SOT stands for “videotape with sound on tape.” However, because one of the strengths of broadcast news is its timeliness-its ability to update a news story as soon as new details are known-it’s often the case that the anchor reads the narration live during the news program itself. The technical notation for live narration is VTR/ VO, that is, “videotape with voice over.”

Straightforward VTR/SOT and short VTR/VO stories are not difficult to execute live. However, the director’s task grows more complicated when VTR/VO segments are edited with VTR/ SOT segments. Ordinarily, these VTR/SOT segments are not reporter narrations but portions of a taped interview or natural sounds that accompany an event (the roar of a rocket launch or music from a marching band).

In these instances, the script must distinguish the SOT portions from the VO portions by noting the exact times for each. In addition, the scriptwriter must also provide an audio outcue (abbreviated OUT -Q) to make sure the director doesn’t clip off a word or two owing to a split-second timing error. When the videotape is rolling, the director must give the audio engineer explicit cues: when to punch up the anchor’s micro- phone (VO) or when to punch up audio on the videotape playback machine (SOT). Just in case the videotape machine fails, scripts often include a summary of SOT segments, often called a precis, so the anchor can ad lib the missing information.

Videotape times are spelled out in detail in the video column of the script. In the example that follows on page 33, the first segment is a 22-second voice-over, followed by an II-second sound bite. The two segments addup to a total running time (TRT) of 33 seconds. In some newsrooms, the practice is to give the length of each segment. The TV-News format presented here designates instead the running time; that is, the time at which each segment begins. Thus, the first voice-over begins at :00, the sound on tape starts at: 22, and the sound bite ends at: 33. The total running time (TRT) is marked opposite the last line of the OUT -Q if the videotape ends with SOT or the last line of the VO copy that the anchor reads. A script could also call for multiple segments of voice-over and sound on tape. If you hear a TV news writer refer to a v-b-v, it means a voice-over, sound bite, voice-over videotape story.

Like Live-TV, TV-News format uses a 35-character, 2-second line for all copy the anchor reads. On camera, time is elastic; that is, the director can hold a studio camera shot indefinitely. But for voice-over copy, the audio reading time must match the videotape running time. If the first segment of silent videotape runs 22 seconds, then the copy for it should run about 11 lines. Ideally, the anchor should finish reading the voice-over in the nick of time with only a beat before the SOT begins. Mismatches in VTR/VO portions of the script create embarrassing errors. Two seconds of silence or one second of black video can seem like forever in a fast-paced news program. Overlapping sound can make even the best-written story incomprehensible.

Two final points about timing: First, don’t confuse the total running time (TRT) of the videotape with the total time of the story. The total story time (sometimes abbreviated TST) includes not only the TRT but also the anchor’s on-camera lead- in and any on-camera tag after the videotape. Second, starting a new paragraph in the audio column is only helpful when it corresponds to a major technical change in the video column.

Otherwise, too many partial lines are created in the script, making it more difficult to estimate how long the voice-over copy actually runs. The editor must make accurate estimates to synchronize audio with video. The producer must make accurate estimates to make sure the entire newscast fits the scheduled time period.