Confidence Interval

Say you were interested in the mean weight of 10-year-old girls living in the United States. Since it would have been impractical to weigh all the 10-year-old girls in the United States, you took a sample of 16 and found that the mean weight was 90 pounds. This sample mean of 90 is a point estimate of the population mean. A point estimate by itself is of limited usefulness because it does not reveal the uncertainty associated with the estimate; you do not have a good sense of how far this sample mean may be from the population mean. For example, can you be confident that the population mean is within 5 pounds of 90? You simply do not know.

Confidence intervals provide more information than point estimates. Confidence intervals for means are intervals constructed using a procedure (presented in the next section) that will contain the population mean a specified proportion of the time, typically either 95% or 99% of the time. These intervals are referred to as 95% and 99% confidence intervals respectively. An example of a 95% confidence interval is shown below:

72.85 < μ < 107.15

There is good reason to believe that the population mean lies between these two bounds of 72.85 and 107.15 since 95% of the time confidence intervals contain the true mean. If repeated samples were taken and the 95% confidence interval computed for each sample, 95% of the intervals would contain the population mean. Naturally, 5% of the intervals would not contain the population mean.

It is natural to interpret a 95% confidence interval as an interval with a 0.95 probability of containing the population mean. However, the proper interpretation is not that simple. One problem is that the computation of a confidence interval does not take into account any other information you might have about the value of the population mean. For example, if numerous prior studies had all found sample means above 110, it would not make sense to conclude that there is a 0.95 probability that the population mean is between 72.85 and 107.15. What about situations in which there is no prior information about the value of the population mean? Even here the interpretation is complex. The problem is that there can be more than one procedure that produces intervals that contain the population parameter 95% of the time. Which procedure produces the “true” 95% confidence interval? Although the various methods are equal from a purely mathematical point of view, the standard method of computing confidence intervals has two desirable properties: each interval is symmetric about the point estimate and each interval is contiguous. Recall from the introductory section in the chapter on probability that, for some purposes, probability is best thought of as subjective. It is reasonable, although not required by the laws of probability, that one adopt a subjective probability of 0.95 that a 95% confidence interval, as typically computed, contains the parameter in question.

Confidence intervals can be computed for various parameters, not just the mean. For example, how to compute a confidence interval for ρ, the population value of Pearson’s r, based on sample data.

Confidence Interval on the Mean

When you compute a confidence interval on the mean, you compute the mean of a sample in order to estimate the mean of the population. Clearly, if you already knew the population mean, there would be no need for a confidence interval. However, to explain how confidence intervals are constructed, we are going to work backwards and begin by assuming characteristics of the population. Then we will show how sample data can be used to construct a confidence interval.

Assume that the weights of 10-year-old children are normally distributed with a mean of 90 and a standard deviation of 36. What is the sampling distribution of the mean for a sample size of 9? Recall from the section on the sampling distribution of the mean that the mean of the sampling distribution is μ and the standard error of the mean is

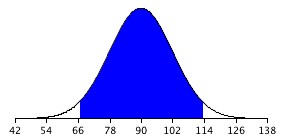

For the present example, the sampling distribution of the mean has a mean of 90 and a standard deviation of 36/3 = 12. Note that the standard deviation of a sampling distribution is its standard error. Figure 1 shows this distribution. The shaded area represents the middle 95% of the distribution and stretches from 66.48 to 113.52. These limits were computed by adding and subtracting 1.96 standard deviations to/from the mean of 90 as follows:

90 – (1.96)(12) = 66.48

90 + (1.96)(12) = 113.52

The value of 1.96 is based on the fact that 95% of the area of a normal distribution is within 1.96 standard deviations of the mean; 12 is the standard error of the mean.

Figure 1. The sampling distribution of the mean for N=9. The middle 95% of the distribution is shaded.

Figure 1 shows that 95% of the means are no more than 23.52 units (1.96 standard deviations) from the mean of 90. Now consider the probability that a sample mean computed in a random sample is within 23.52 units of the population mean of 90. Since 95% of the distribution is within 23.52 of 90, the probability that the mean from any given sample will be within 23.52 of 90 is 0.95. This means that if we repeatedly compute the mean (M) from a sample, and create an interval ranging from M – 23.52 to M + 23.52, this interval will contain the population mean 95% of the time. In general, you compute the 95% confidence interval for the mean with the following formula

Lower limit = M – Z.95σM

Upper limit = M + Z.95σM

where Z.95 is the number of standard deviations extending from the mean of a normal distribution required to contain 0.95 of the area and σM is the standard error of the mean. If you look closely at this formula for a confidence interval, you will notice that you need to know the standard deviation (σ) in order to estimate the mean. This may sound unrealistic, and it is. However, computing a confidence interval when σ is known is easier than when σ has to be estimated, and serves a pedagogical purpose. Later in this section we will show how to compute a confidence interval for the mean when σ has to be estimated.

Suppose the following five numbers were sampled from a normal distribution with a standard deviation of 2.5: 2, 3, 5, 6, and 9. To compute the 95% confidence interval, start by computing the mean and standard error:

M = (2 + 3 + 5 + 6 + 9)/5 = 5.

σM =![]() = 1.118.

= 1.118.

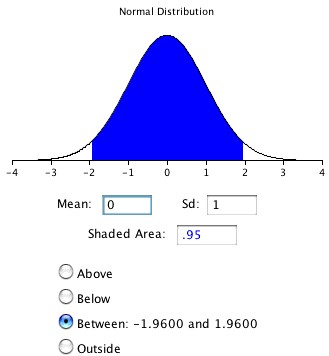

Z.95 can be found using the normal distribution calculator and specifying that the shaded area is 0.95 and indicating that you want the area to be between the cutoff points. As shown in Figure 2, the value is 1.96. If you had wanted to compute the 99% confidence interval, you would have set the shaded area to 0.99 and the result would have been 2.58.

The confidence interval can then be computed as follows:

Lower limit = 5 – (1.96)(1.118)= 2.81

Upper limit = 5 + (1.96)(1.118)= 7.19

You should use the t distribution rather than the normal distribution when the variance is not known and has to be estimated from sample data. When the sample size is large, say 100 or above, the t distribution is very similar to the standard normal distribution. However, with smaller sample sizes, the t distribution is leptokurtic, which means it has relatively more scores in its tails than does the normal distribution. As a result, you have to extend farther from the mean to contain a given proportion of the area. Recall that with a normal distribution, 95% of the distribution is within 1.96 standard deviations of the mean. Using the t distribution, if you have a sample size of only 5, 95% of the area is within 2.78 standard deviations of the mean. Therefore, the standard error of the mean would be multiplied by 2.78 rather than 1.96.

The values of t to be used in a confidence interval can be looked up in a table of the t distribution. A small version of such a table is shown in Table 1. The first column, df, stands for degrees of freedom, and for confidence intervals on the mean, df is equal to N – 1, where N is the sample size.

| df | 0.95 | 0.99 |

| 2 | 4.303 | 9.925 |

| 3 | 3.182 | 5.841 |

| 4 | 2.776 | 4.604 |

| 5 | 2.571 | 4.032 |

| 8 | 2.306 | 3.355 |

| 10 | 2.228 | 3.169 |

| 20 | 2.086 | 2.845 |

| 50 | 2.009 | 2.678 |

| 100 | 1.984 | 2.626 |

Table 1. Abbreviated t table.

You can also use the “inverse t distribution” calculator to find the t values to use in confidence intervals. You will learn more about the t distribution in the next section. Assume that the following five numbers are sampled from a normal distribution: 2, 3, 5, 6, and 9 and that the standard deviation is not known. The first steps are to compute the sample mean and variance:

M = 5

s2 = 7.5

The next step is to estimate the standard error of the mean. If we knew the population variance, we could use the following formula:

Instead we compute an estimate of the standard error (sM):

![]() =1.225

=1.225

The next step is to find the value of t. As you can see from Table 1, the value for the 95% interval for df = N – 1 = 4 is 2.776. The confidence interval is then computed just as it is when σM. The only differences are that sM and t rather than σM and Z are used.

Lower limit = 5 – (2.776)(1.225) = 1.60

Upper limit = 5 + (2.776)(1.225) = 8.40

More generally, the formula for the 95% confidence interval on the mean is:

Lower limit = M – (tCL)(sM)

Upper limit = M + (tCL)(sM)

where M is the sample mean, tCL is the t for the confidence level desired (0.95 in the above example), and sM is the estimated standard error of the mean.

We will finish with an analysis of the Stroop Data. Specifically, we will compute a confidence interval on the mean difference score. Recall that 47 subjects named the color of ink that words were written in. The names conflicted so that, for example, they would name the ink color of the word “blue” written in red ink. The correct response is to say “red” and ignore the fact that the word is “blue.” In a second condition, subjects named the ink color of colored rectangles.

| Naming Colored Rectangle | Interference | Difference |

| 17 | 38 | 21 |

| 15 | 58 | 43 |

| 18 | 35 | 17 |

| 20 | 39 | 19 |

| 18 | 33 | 15 |

| 20 | 32 | 12 |

| 20 | 45 | 25 |

| 19 | 52 | 33 |

| 17 | 31 | 14 |

| 21 | 29 | 8 |

Table 2. Response times in seconds for 10 subjects.

Table 2 shows the time difference between the interference and color-naming conditions for 10 of the 47 subjects. The mean time difference for all 47 subjects is 16.362 seconds and the standard deviation is 7.470 seconds. The standard error of the mean is 1.090. A t table shows the critical value of t for 47 – 1 = 46 degrees of freedom is 2.013 (for a 95% confidence interval). Therefore the confidence interval is computed as follows:

Lower limit = 16.362 – (2.013)(1.090) = 14.17

Upper limit = 16.362 + (2.013)(1.090) = 18.56

Therefore, the interference effect (difference) for the whole population is likely to be between 14.17 and 18.56 seconds.