A rootkit is a stealthy type of software, typically malicious, designed to hide the existence of certain processes or programs from normal methods of detection and enable continued privileged access to a computer. The term rootkit is a concatenation of “root” (the traditional name of the privileged account on Unix operating systems) and the word “kit” (which refers to the software components that implement the tool). The term “rootkit” has negative connotations through its association with malware.

Rootkit installation can be automated, or an attacker can install it once they’ve obtained root or Administrator access. Obtaining this access is a result of direct attack on a system (i.e.), exploiting a known vulnerability (such as privilege escalation) or a password (obtained by cracking or social engineering). Once installed, it becomes possible to hide the intrusion as well as to maintain privileged access. The key is the root or Administrator access. Full control over a system means that existing software can be modified, including software that might otherwise be used to detect or circumvent it.

Rootkit detection is difficult because a rootkit may be able to subvert the software that is intended to find it. Detection methods include using an alternative and trusted operating system, behavioral-based methods, signature scanning, difference scanning, and memory dump analysis. Removal can be complicated or practically impossible, especially in cases where the rootkit resides in the kernel; reinstallation of the operating system may be the only available solution to the problem. When dealing with firmware rootkits, removal may require hardware replacement, or specialized equipment.

Uses

Modern rootkits do not elevate access, but rather are used to make another software payload undetectable by adding stealth capabilities. Most rootkits are classified as malware, because the payloads they are bundled with are malicious. For example, a payload might covertly steal user passwords, credit card information, computing resources, or conduct other unauthorized activities. A small number of rootkits may be considered utility applications by their users: for example, a rootkit might cloak a CD-ROM-emulation driver, allowing video game users to defeat anti-piracy measures that require insertion of the original installation media into a physical optical drive to verify that the software was legitimately purchased, which can be very inconvenient even to those who did legitimately purchase it.

Rootkits and their payloads have many uses:

- Provide an attacker with full access via a backdoor, permitting unauthorized access to, for example, steal or falsify documents. One of the ways to carry this out is to subvert the login mechanism, such as the /bin/login program on Unix-like systems or GINA on Windows. The replacement appears to function normally, but also accepts a secret login combination that allows an attacker direct access to the system with administrative privileges, bypassing standard authentication and authorization mechanisms.

- Conceal other malware, notably password-stealing key loggers and computer viruses.

- Appropriate the compromised machine as a zombie computer for attacks on other computers. (The attack originates from the compromised system or network, instead of the attacker’s system.) “Zombie” computers are typically members of large botnets that can launch denial-of-service attacks, distribute e-mail spam, conduct click fraud, etc.

- Enforcement of digital rights management (DRM).

In some instances, rootkits provide desired functionality, and may be installed intentionally on behalf of the computer user:

- Conceal cheating in online games from software like Warden.

- Detect attacks, for example, in a honeypot.

- Enhance emulation software and security software. Alcohol 120% and Daemon Tools are commercial examples of non-hostile rootkits used to defeat copy-protection mechanisms such as SafeDisc and SecuROM. Kaspersky antivirus software also uses techniques resembling rootkits to protect itself from malicious actions. It loads its own drivers to intercept system activity, and then prevents other processes from doing harm to itself. Its processes are not hidden, but cannot be terminated by standard methods (It can be terminated with Process Hacker).

- Anti-theft protection: Laptops may have BIOS-based rootkit software that will periodically report to a central authority, allowing the laptop to be monitored, disabled or wiped of information in the event that it is stolen.

- Bypassing Microsoft Product Activation

Types

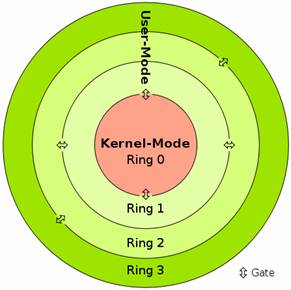

There are at least five types of rootkit, ranging from those at the lowest level in firmware (with the highest privileges), through to the least privileged user-based variants that operate in Ring 3. Hybrid combinations of these may occur spanning, for example, user mode and kernel mode.

User mode – User-mode rootkits run in Ring 3, along with other applications as user, rather than low-level system processes. They have a number of possible installation vectors to intercept and modify the standard behavior of application programming interfaces (APIs). Some inject a dynamically linked library (such as a .DLL file on Windows, or a .dylib file on Mac OS X) into other processes, and are thereby able to execute inside any target process to spoof it; others with sufficient privileges simply overwrite the memory of a target application. Injection mechanisms include:

- Use of vendor-supplied application extensions. For example, Windows Explorer has public interfaces that allow third parties to extend its functionality.

- Interception of messages.

- Exploitation of security vulnerabilities.

- Function hooking or patching of commonly used APIs, for example, to hide a running process or file that resides on a filesystem.

Since user mode applications all run in their own memory space, the rootkit needs to perform this patching in the memory space of every running application. In addition, the rootkit needs to monitor the system for any new applications that execute and patch those programs’ memory space before they fully execute.

Kernel mode – Kernel-mode rootkits run with the highest operating system privileges (Ring 0) by adding code or replacing portions of the core operating system, including both the kernel and associated device drivers. Most operating systems support kernel-mode device drivers, which execute with the same privileges as the operating system itself. As such, many kernel-mode rootkits are developed as device drivers or loadable modules, such as loadable kernel modules in Linux or device drivers in Microsoft Windows. This class of rootkit has unrestricted security access, but is more difficult to write. The complexity makes bugs common, and any bugs in code operating at the kernel level may seriously impact system stability, leading to discovery of the rootkit. One of the first widely known kernel rootkits was developed for Windows NT 4.0 and released in Phrack magazine in 1999 by Greg Hoglund.

Kernel rootkits can be especially difficult to detect and remove because they operate at the same security level as the operating system itself, and are thus able to intercept or subvert the most trusted operating system operations. Any software, such as antivirus software, running on the compromised system is equally vulnerable. In this situation, no part of the system can be trusted.

A rootkit can modify data structures in the Windows kernel using a method known as direct kernel object manipulation (DKOM). This method can be used to hide processes. A kernel mode rootkit can also hook the System Service Descriptor Table (SSDT), or modify the gates between user mode and kernel mode, in order to cloak itself. Similarly for the Linux operating system, a rootkit can modify the system call table to subvert kernel functionality. It’s common that a rootkit creates a hidden, encrypted filesystem in which it can hide other malware or original copies of files it has infected.

Operating systems are evolving to counter the threat of kernel-mode rootkits. For example, 64-bit editions of Microsoft Windows now implement mandatory signing of all kernel-level drivers in order to make it more difficult for untrusted code to execute with the highest privileges in a system.

Bootkits – A kernel-mode rootkit variant called a bootkit can infect startup code like the Master Boot Record (MBR), Volume Boot Record (VBR) or boot sector, and in this way, can be used to attack full disk encryption systems. An example is the “Evil Maid Attack”, in which an attacker installs a bootkit on an unattended computer, replacing the legitimate boot loader with one under his control. Typically the malware loader persists through the transition to protected mode when the kernel has loaded, and is thus able to subvert the kernel. For example, the “Stoned Bootkit” subverts the system by using a compromised boot loader to intercept encryption keys and passwords. More recently, the Alureon rootkit has successfully subverted the requirement for 64-bit kernel-mode driver signing in Windows 7 by modifying the master boot record. Although not malware in the sense of doing something the user doesn’t want, certain “Vista Loader” or “Windows Loader” software works in a similar way by injecting an ACPI SLIC (System Licensed Internal Code) table in the RAM-cached version of the BIOS during boot, in order to defeat the Windows Vista and Windows 7 activation process. This vector of attack was rendered useless in the (non-server) versions of Windows 8, which use a unique, machine-specific key for each system, that can only be used by that one machine.

The only known defenses against bootkit attacks are the prevention of unauthorized physical access to the system—a problem for portable computers—or the use of a Trusted Platform Module configured to protect the boot path.

Hypervisor Level – Rootkits have been created as Type II Hypervisors in academia as proofs of concept. By exploiting hardware virtualization features such as Intel VT or AMD-V, this type of rootkit runs in Ring -1 and hosts the target operating system as a virtual machine, thereby enabling the rootkit to intercept hardware calls made by the original operating system. Unlike normal hypervisors, they do not have to load before the operating system, but can load into an operating system before promoting it into a virtual machine. A hypervisor rootkit does not have to make any modifications to the kernel of the target to subvert it; however, that does not mean that it cannot be detected by the guest operating system. For example, timing differences may be detectable in CPU instructions. The “SubVirt” laboratory rootkit, developed jointly by Microsoft and University of Michigan researchers, is an academic example of a virtual machine–based rootkit (VMBR), while Blue Pill is another.

In 2009, researchers from Microsoft and North Carolina State University demonstrated a hypervisor-layer anti-rootkit called Hooksafe, which provides generic protection against kernel-mode rootkits.

Firmware and Hardware – A firmware rootkit uses device or platform firmware to create a persistent malware image in hardware, such as a router, network card, hard drive, or the system BIOS. The rootkit hides in firmware, because firmware is not usually inspected for code integrity. John Heasman demonstrated the viability of firmware rootkits in both ACPI firmware routines and in a PCI expansion card ROM.

In October 2008, criminals tampered with European credit-card-reading machines before they were installed. The devices intercepted and transmitted credit card details via a mobile phone network. In March 2009, researchers Alfredo Ortega and Anibal Sacco published details of a BIOS-level Windows rootkit that was able to survive disk replacement and operating system re-installation. A few months later they learned that some laptops are sold with a legitimate rootkit, known as Absolute CompuTrace or Absolute LoJack for Laptops, preinstalled in many BIOS images. This is an anti-theft technology system that researchers showed can be turned to malicious purposes.

Intel Active Management Technology, part of Intel vPro, implements out-of-band management, giving administrators remote administration, remote management, and remote control of PCs with no involvement of the host processor or BIOS, even when the system is powered off. Remote administration includes remote power-up and power-down, remote reset, redirected boot, console redirection, pre-boot access to BIOS settings, programmable filtering for inbound and outbound network traffic, agent presence checking, out-of-band policy-based alerting, access to system information, such as hardware asset information, persistent event logs, and other information that is stored in dedicated memory (not on the hard drive) where it is accessible even if the OS is down or the PC is powered off. Some of these functions require the deepest level of rootkit, a second non-removable spy computer built around the main computer. Sandy Bridge and future chipsets have “the ability to remotely kill and restore a lost or stolen PC via 3G”. Hardware rootkits built into the chipset can help recover stolen computers, remove data, or render them useless, but they also present privacy and security concerns of undetectable spying and redirection by management or hackers who might gain control.

Installation and cloaking

Rootkits employ a variety of techniques to gain control of a system; the type of rootkit influences the choice of attack vector. The most common technique leverages security vulnerabilities to achieve surreptitious privilege escalation. Another approach is to use a Trojan horse, deceiving a computer user into trusting the rootkit’s installation program as benign—in this case, social engineering convinces a user that the rootkit is beneficial. The installation task is made easier if the principle of least privilege is not applied, since the rootkit then does not have to explicitly request elevated (administrator-level) privileges. Other classes of rootkits can be installed only by someone with physical access to the target system. Some rootkits may also be installed intentionally by the owner of the system or somebody authorized by the owner, e.g. for the purpose of employee monitoring, rendering such subversive techniques unnecessary.

The installation of malicious rootkits is commercially driven, with a pay-per-install (PPI) compensation method typical for distribution.

Once installed, a rootkit takes active measures to obscure its presence within the host system through subversion or evasion of standard operating system security tools and APIs used for diagnosis, scanning, and monitoring. Rootkits achieve this by modifying the behavior of core parts of an operating system through loading code into other processes, the installation or modification of drivers, or kernel modules. Obfuscation techniques include concealing running processes from system-monitoring mechanisms and hiding system files and other configuration data. It is not uncommon for a rootkit to disable the event logging capacity of an operating system, in an attempt to hide evidence of an attack. Rootkits can, in theory, subvert any operating system activities. The “perfect rootkit” can be thought of as similar to a “perfect crime”: one that nobody realizes has taken place.

Rootkits also take a number of measures to ensure their survival against detection and cleaning by antivirus software in addition to commonly installing into Ring 0 (kernel-mode), where they have complete access to a system. These include polymorphism, stealth techniques, regeneration, and disabling anti-malware software.

Defenses

System hardening represents one of the first layers of defence against a rootkit, to prevent it from being able to install. Applying security patches, implementing the principle of least privilege, reducing the attack surface and installing antivirus software are some standard security best practices that are effective against all classes of malware.

New secure boot specifications like Unified Extensible Firmware Interface are currently being designed to address the threat of bootkits.

For server systems, remote server attestation using technologies such as Intel Trusted Execution Technology (TXT) provide a way of validating that servers remain in a known good state. For example, Microsoft Bitlocker encrypting data-at-rest validates servers are in a known “good state” on bootup. PrivateCore vCage is a software offering that secures data-in-use (memory) to avoid bootkits and rootkits by validating servers are in a known “good” state on bootup. The PrivateCore implementation works in concert with Intel TXT and locks down server system interfaces to avoid potential bootkits and rootkits.

Detection

The fundamental problem with rootkit detection is that if the operating system has been subverted, particularly by a kernel-level rootkit, it cannot be trusted to find unauthorized modifications to itself or its components. Actions such as requesting a list of running processes, or a list of files in a directory, cannot be trusted to behave as expected. In other words, rootkit detectors that work while running on infected systems are only effective against rootkits that have some defect in their camouflage, or that run with lower user-mode privileges than the detection software in the kernel. As with computer viruses, the detection and elimination of rootkits is an ongoing struggle between both sides of this conflict.

Detection can take a number of different approaches, including signatures (e.g. antivirus software), integrity checking (e.g. digital signatures), difference-based detection (comparison of expected vs. actual results), and behavioral detection (e.g. monitoring CPU usage or network traffic). For kernel-mode rootkits, detection is considerably more complex, requiring careful scrutiny of the System Call Table to look for hooked functions where the malware may be subverting system behavior, as well as forensic scanning of memory for patterns that indicate hidden processes.

Unix rootkit detection offerings include Zeppoo, chkrootkit, rkhunter and OSSEC. For Windows, detection tools include Microsoft Sysinternals RootkitRevealer, Avast! Antivirus, Sophos Anti-Rootkit, F-Secure, Radix, GMER, and WindowsSCOPE. Any rootkit detectors that prove effective ultimately contribute to their own ineffectiveness, as malware authors adapt and test their code to escape detection by well-used tools.

Detection by examining storage while the suspect operating system is not operational can miss rootkits not recognised by the checking software, as the rootkit is not active and suspicious behavior is suppressed; conventional anti-malware software running with the rootkit operational may fail if the rootkit hides itself effectively.

Alternative trusted medium – The best and most reliable method for operating-system-level rootkit detection is to shut down the computer suspected of infection, and then to check its storage by booting from an alternative trusted medium (e.g. a rescue CD-ROM or USB flash drive). The technique is effective because a rootkit cannot actively hide its presence if it is not running.

Behavioral-based – The behavioral-based approach to detecting rootkits attempts to infer the presence of a rootkit by looking for rootkit-like behavior. For example, by profiling a system, differences in the timing and frequency of API calls or in overall CPU utilization can be attributed to a rootkit. The method is complex and is hampered by a high incidence of false positives. Defective rootkits can sometimes introduce very obvious changes to a system: the Alureon rootkit crashed Windows systems after a security update exposed a design flaw in its code.

Logs from a packet analyzer, firewall, or intrusion prevention system may present evidence of rootkit behaviour in a networked environment.

Signature-based – Antivirus products rarely catch all viruses in public tests (depending on what is used and to what extent), even though security software vendors incorporate rootkit detection into their products. Should a rootkit attempt to hide during an antivirus scan, a stealth detector may notice; if the rootkit attempts to temporarily unload itself from the system, signature detection (or “fingerprinting”) can still find it. This combined approach forces attackers to implement counterattack mechanisms, or “retro” routines, that attempt to terminate antivirus programs. Signature-based detection methods can be effective against well-published rootkits, but less so against specially crafted, custom-root rootkits.

Difference-based – Another method that can detect rootkits compares “trusted” raw data with “tainted” content returned by an API. For example, binaries present on disk can be compared with their copies within operating memory (in some operating systems, the in-memory image should be identical to the on-disk image), or the results returned from file system or Windows Registry APIs can be checked against raw structures on the underlying physical disks — however, in the case of the former, some valid differences can be introduced by operating system mechanisms like memory relocation or shimming. A rootkit may detect the presence of a such difference-based scanner or virtual machine (the latter being commonly used to perform forensic analysis), and adjust its behaviour so that no differences can be detected. Difference-based detection was used by Russinovich’s RootkitRevealer tool to find the Sony DRM rootkit.

Integrity checking – The rkhunter utility uses SHA-1 hashes to verify the integrity of system files. Code signing uses public-key infrastructure to check if a file has been modified since being digitally signed by its publisher. Alternatively, a system owner or administrator can use a cryptographic hash function to compute a “fingerprint” at installation time that can help to detect subsequent unauthorized changes to on-disk code libraries. However, unsophisticated schemes check only whether the code has been modified since installation time; subversion prior to that time is not detectable. The fingerprint must be re-established each time changes are made to the system: for example, after installing security updates or a service pack. The hash function creates a message digest, a relatively short code calculated from each bit in the file using an algorithm that creates large changes in the message digest with even smaller changes to the original file. By recalculating and comparing the message digest of the installed files at regular intervals against a trusted list of message digests, changes in the system can be detected and monitored—as long as the original baseline was created before the malware was added. More-sophisticated rootkits are able to subvert the verification process by presenting an unmodified copy of the file for inspection, or by making code modifications only in memory, rather than on disk. The technique may therefore be effective only against unsophisticated rootkits—for example, those that replace Unix binaries like “ls” to hide the presence of a file.

Similarly, detection in firmware can be achieved by computing a cryptographic hash of the firmware and comparing it to a whitelist of expected values, or by extending the hash value into Trusted Platform Module (TPM) configuration registers, which are later compared to a whitelist of expected values. The code that performs hash, compare, or extend operations must also be protected—in this context, the notion of an immutable root-of-trust holds that the very first code to measure security properties of a system must itself be trusted to ensure that a rootkit or bootkit does not compromise the system at its most fundamental level.

Memory dumps – Forcing a complete dump of virtual memory will capture an active rootkit (or a kernel dump in the case of a kernel-mode rootkit), allowing offline forensic analysis to be performed with a debugger against the resulting dump file, without the rootkit being able to take any measures to cloak itself. This technique is highly specialized, and may require access to non-public source code or debugging symbols. Memory dumps initiated by the operating system cannot always be used to detect a hypervisor-based rootkit, which is able to intercept and subvert the lowest-level attempts to read memory —a hardware device, such as one that implements a non-maskable interrupt, may be required to dump memory in this scenario.