The payback (PB) is one of most popular and widely recognized traditional methods of evaluating investment proposals. It is defined as the number of years required to recover the original cash outlay invested in the project. If the project generates constant annual cash inflows, the payback period can be computed by dividing the cash outlay by the annual cash inflow.

Acceptance Rule

Many firms use the payback period as accept or reject criterion as well as method of ranking projects. If the payback period calculated for a project is less than the maximum payback period set by management, it would be accepted; if not it would be rejected. As a ranking method, it gives highest ranking to the project, which has shortest payback period, and lowest ranking to the project with highest payback period. Thus if the firm has to choose between two mutually exclusive projects, project with shorter payback period will be selected.

Evaluation of Payback

The most significant merit of payback is that it is simple to understand and easy to calculate. The business executives consider the simplicity of method as a virtue, which is evident from their heavy reliance on it for appraising investment proposals in practice. Another merit is that it costs less than most of the sophisticated techniques, which require a lot of the analysis time and the use of computers.

Limitation

In spite of its simplicity, the payback may not be a desirable investment criterion since it suffers from a number of serious limitations

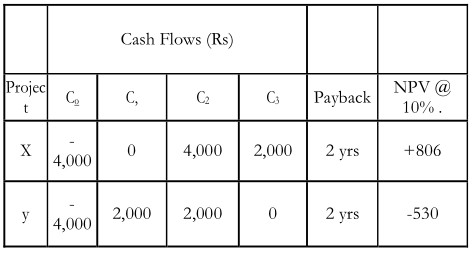

- It fails to take account of the cash inflows earned after the payback period. For example, consider the following projects

- Despite its appeal for some reasons, the payback period analysis method has some significant drawbacks. The first is that it fails to take into account the time value of money and adjust the cash inflows accordingly.

- The payback analysis fails to consider inflows of cash that occur beyond the payback period, thus failing to compare the overall profitability of one project as compared to another.

- The simplicity of the payback period analysis falls short in not taking into account the complexity of cash flows that can occur with capital investments.

As per the payback rule, both the projects are equally desirable since both return the investment outlay in two years. If we assume an opportunity cost of 10 per cent, Project X yields a positive net present value of Rs 806 and Project Y yields a negative net present value of Rs 530. As per the NPV rule, Project X should be accepted and Project Y rejected. Payback rule gave wrong results because it failed to consider Rs 2,000 cash flow in third year for Project X.

- It is not an appropriate method of measuring the profitability of an investment project as it does not consider all cash inflows yielded by the project Considering Project X again, payback rule did not take into account its entire series of cash flows.

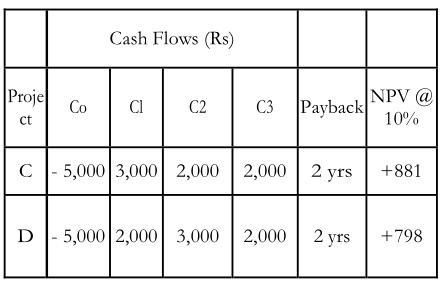

It fails to consider the pattern of cash inflows, i.e., magnitude and timing of cash inflows. In other words, it gives equal weights to returns of equal amounts even though they occur in different time periods. For example, compare the following projects C and D where they involve equal cash outlay and yield equal total cash inflows over equal time periods:

- Using payback period, both projects are equally desirable. But Project C should be preferable as larger cash inflows come earlier in its life. This is indicated by the NPV rule; project C has higher NPV (Rs 881) than Project D (Rs 798) at 10 per cent opportunity cost It should be thus clear that payback is not a measure of profitability. As such, it is dangerous to use it as a decision criterion.

- Administrative difficulties may be faced in determining the maximum acceptable payback period. There is no rational basis for setting a maximum payback period. It is generally a subjective decision.

- The payback period method is not consistent with the objective of maximizing the market value of the firm’s shares. Share values do not depend on payback periods of investment projects.1

Despite its weakness, payback period method is popular in practice. Besides simplicity the causes for its popularity are:

- A company can have more favorable short-run effects on earnings per share by setting up a shorter standard payback period? It should, however, be remembered that this may not be a wise long-term policy as company may have to sacrifice its future growth for current earnings.

- The riskiness of the project can be tackled by having a short term standard payback period as it may ensure guarantee against loss. A company has to invest in many projects where the cash inflows and life expectancies are highly uncertain. Under such circumstances, payback may much as a measure of profitability but as a means of establishing an upper bound on the acceptable degree of risk.

- The emphasis in payback is on the early recovery of the investment Thus, it gives an insight into the liquidity of the project. The funds so released can be put to other uses.

Let us re-emphasize that the payback is not a valid method for evaluating the accept-ability of the investment projects. It can, however, be used along with the NPV rule as a first Step in roughly screening the projects. In practice, the use of DCF techniques has been increasing but payback continues to remain a popular and primary method of investment evaluation.