Public Key Infrastructure

Public-key cryptography (also called asymmetric-key cryptography) uses a key pair to encrypt and decrypt content. The key pair consists of one public and one private key that are mathematically related. An individual who intends to communicate securely with others can distribute the public key but must keep the private key secret. Content encrypted by using one of the keys can be decrypted by using the other. Assume, for example, that Bob wants to send a secure email message to Alice. This can be accomplished in the following manner

- Both Bob and Alice have their own key pairs. They have kept their private keys securely to themselves and have sent their public keys directly to each other.

- Bob uses Alice’s public key to encrypt the message and sends it to her.

- Alice uses her private key to decrypt the message.

This simplified example highlights at least one obvious concern Bob must have about the public key he used to encrypt the message. That is, he cannot know with certainty that the key he used for encryption actually belonged to Alice. It is possible that another party monitoring the communication channel between Bob and Alice substituted a different key.

The public key infrastructure concept has evolved to help address this problem and others. A public key infrastructure (PKI) consists of software and hardware elements that a trusted third party can use to establish the integrity and ownership of a public key. The trusted party, called a certification authority (CA), typically accomplishes this by issuing signed (encrypted) binary certificates that affirm the identity of the certificate subject and bind that identity to the public key contained in the certificate. The CA signs the certificate by using its private key. It issues the corresponding public key to all interested parties in a self-signed CA certificate. When a CA is used, the preceding example can be modified in the following manner

- Assume that the CA has issued a signed digital certificate that contains its public key. The CA self-signs this certificate by using the private key that corresponds to the public key in the certificate.

- Alice and Bob agree to use the CA to verify their identities.

- Alice requests a public key certificate from the CA.

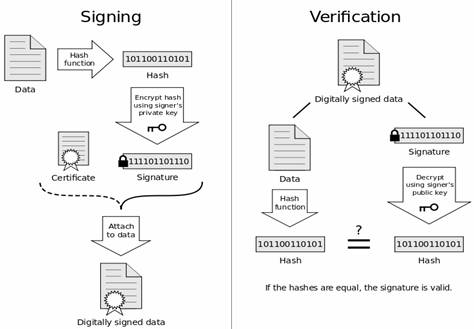

- The CA verifies her identity, computes a hash of the content that will make up her certificate, signs the hash by using the private key that corresponds to the public key in the published CA certificate, creates a new certificate by concatenating the certificate content and the signed hash, and makes the new certificate publicly available.

- Bob retrieves the certificate, decrypts the signed hash by using the public key of the CA, computes a new hash of the certificate content, and compares the two hashes. If the hashes match, the signature is verified and Bob can assume that the public key in the certificate does indeed belong to Alice.

- Bob uses Alice’s verified public key to encrypt a message to her.

- Alice uses her private key to decrypt the message from Bob.

In summary, the certificate signing process enables Bob to verify that the public key was not tampered with or corrupted during transit. Before issuing a certificate, the CA hashes the contents, signs (encrypts) the hash by using its own private key, and includes the encrypted hash in the issued certificate. Bob verifies the certificate contents by decrypting the hash with the CA public key, performing a separate hash of the certificate contents, and comparing the two hashes. If they match, Bob can be reasonably certain that the certificate and the public key it contains have not been altered. A typical PKI consists of the following elements.

| Element | Description |

| Certification Authority | Acts as the root of trust in a public key infrastructure and provides services that authenticate the identity of individuals, computers, and other entities in a network. |

| Registration Authority | Is certified by a root CA to issue certificates for specific uses permitted by the root. In a Microsoft PKI, a registration authority (RA) is usually called a subordinate CA. |

| Certificate Database | Saves certificate requests and issued and revoked certificates and certificate requests on the CA or RA. |

| Certificate Store | Saves issued certificates and pending or rejected certificate requests on the local computer. |

| Key Archival Server | Saves encrypted private keys in the certificate database for recovery after loss. |

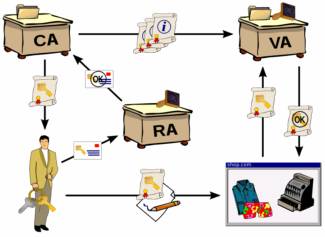

PKI is an arrangement that binds public keys with respective user identities by means of a certificate authority (CA). The user identity must be unique within each CA domain. The third-party validation authority (VA) can provide this information on behalf of CA. The binding is established through the registration and issuance process, which, depending on the assurance level of the binding, may be carried out by software at a CA or under human supervision. The PKI role that assures this binding is called the registration authority (RA), which ensures that the public key is bound to the individual to which it is assigned in a way that ensures non-repudiation.

Digital Signature

A digital signature is a mathematical scheme for demonstrating the authenticity of a digital message or document. A valid digital signature gives a recipient reason to believe that the message was created by a known sender, such that the sender cannot deny having sent the message (authentication and non-repudiation) and that the message was not altered in transit (integrity). Digital signatures are commonly used for software distribution, financial transactions, and in other cases where it is important to detect forgery or tampering.

Digital signatures are often used to implement electronic signatures, but not all electronic signatures use digital signatures. In some countries, including the United States, India, Brazil, and members of the European Union, electronic signatures have legal significance.

Digital signatures employ a type of asymmetric cryptography. For messages sent through a non-secure channel, a properly implemented digital signature gives the receiver reason to believe the message was sent by the claimed sender. Digital signatures are equivalent to traditional handwritten signatures in many respects, but properly implemented digital signatures are more difficult to forge than the handwritten type. Digital signature schemes, in the sense used here, are cryptographically based, and must be implemented properly to be effective. Digital signatures can also provide non-repudiation, meaning that the signer cannot successfully claim they did not sign a message, while also claiming their private key remains secret; further, some non-repudiation schemes offer a time stamp for the digital signature, so that even if the private key is exposed, the signature is valid. Digitally signed messages may be anything represented as a string of bits like electronic mail, contracts, or a message sent via some other cryptographic protocol. A digital signature scheme typically consists of three algorithms

- A key generation algorithm that selects a private key uniformly at random from a set of possible private keys. The algorithm outputs the private key and a corresponding public key.

- A signing algorithm that, given a message and a private key, produces a signature.

- A signature verifying algorithm that, given a message, public key and a signature, either accepts or rejects the message’s claim to authenticity.

Two main properties are required. First, the authenticity of a signature generated from a fixed message and fixed private key can be verified by using the corresponding public key. Secondly, it should be computationally infeasible to generate a valid signature for a party without knowing that party’s private key.