At this stage of the analysis, the channel manager is equipped to decide what segments to target. Note carefully that this also means that the channel manager is now equipped to decide what segments not to target! Knowing what segments to ignore in one’s channel design and management efforts is very important, because it keeps the channel focused on the key segments from which it plans to reap profitable sales.

Why not target all the segments identified in the segmentation and positioning analyses? The answer requires the channel manager to look at the internal and external environment facing the channel. Internally, managerial bounds may constrain the channel manager from implementing the zero-based channel. For example, top management of a manufacturing firm may be unwilling to allocate funds to build a series of regional ware- houses that would be necessary to provide spatial convenience in a particular market situation. Externally, both environmental bounds and competitive benchmarks may suggest some segments as higher priority than others. For example, legal practices can constrain channel design and hence targeting decisions. Many countries restrict the opening of large mass- merchandise stores in urban areas, to protect small shopkeepers whose sales would be threatened by larger retailers. Such legal restrictions can lead to a channel design that does not appropriately meet the target segment’s service output demands, and may cause a channel manager to avoid targeting that segment entirely.

Of course, the corollary of this statement is that when superior competitive offerings do not exist to serve a particular segment’s demands for service outputs, the channel manager may recognize an unexploited market opportunity and create a new channel to serve that underserved segment. Meeting previously unmet service output demands can be a powerful competitive strategy for building loyal and profitable consumer bases in a marketplace. But these strategies can best be identified with knowledge of what consumers want to buy, and importantly, how they want to buy it, and the necessary response in terms of channel flow performance and channel structure.

We have now identified a subset of the market’s segments that the channel plans on targeting, using the segmentation and positioning insights derived earlier.

Channel Design: Establish New Channels or Refine Existing Channels: Now, the channel manager has identified the ‘optimal way to reach each targeted segment in the market, and has also identified the bounds that might prevent the channel from implementing. the zero-based channel design in the market. If no channel exists currently in the market for this segment, the channel manager should now establish the channel design that comes the closest to meeting the target market’s demands for, service outputs, subject to the environmental and managerial bounds constraining the design.

If there is a preexisting channel in place in the market, however, the channel manager should now perform a gap analysis. The differences between the zero-based and actual channels on the demand and supply sides constitute gaps in the channel design. Gaps can exist on the demand side or on the supply side.

On the demand side, gaps mean that the service output demands is not being appropriately met by the channel. The service output in question may be either undersupplied or oversupplied. The problem is obvious in the case of undersupply: The target segment is likely to be dissatisfied because end-users would prefer more service than they are getting. The problem is more subtle in the case of oversupply. Here, target end-users are getting all the service they desire-and then some. The problem is that service is costly to supply, and therefore, supplying too much of it leads to higher prices than the target end-users are likely to be willing to pay. Clearly, more than one service output may be a problem, in which case several gaps may need attention.

On the supply side, gaps mean that at least one. flow in the channel of distribution is carried out at too high a cost. This not only wastes channel profit margins, but can result in higher prices than the target market is willing to pay, leading to reductions in sales and market share. Supply-side gaps can result from a lack of up-to-date expertise in channel now management or simply from waste in the channel The challenge in closing a supply-side gap is to reduce cost without dangerous])’ reducing the service outputs being supplied to target end-users.

When gaps are identified on the demand or supply sides, several strategies are available for closing the gaps. But once a channel is already in place, it may be very difficult and costly to close these gaps. This suggests the strategic importance of initial channel design. If the channel is initially designed in a haphazard manner, channel members may have to live with a suboptimal channel later on, even after recognizing channel gaps and making best efforts to close them.

Channel Implementation: Identifying Power Sources: assuming that a good channel design is in place in the market, the channel-manager’s job is still not done. The channel members now must implement the optimal channel design and indeed must continue to implement an optimal design through time. The value of doing so might seem to be self- evident, but it is important to remember that a channel is made up of multiple interdependent entities (companies, agents, individuals). But they mayor ma)’ not all have the same incentives to implement the optimal channel design.

Incompatible incentives among channel members would not be a problem if they were not dependent upon each other. But by the very nature of the distribution channel structure and design, specific channel members are likely to specialize in particular activities and flows in the channel. If all channel members do not perform appropriately, the entire channel effort suffers. For example, even if everything else is in place, a poorly performing transportation system that results in late deliveries (or no deliveries) of product to retail stores prevents the channel from succeeding in selling the product. The same type of statement could be made about the performance of any channel member doing any of the flows in the channel Thus, it is apparent that inducing all of the channel members to implement the channel design appropriately is critical.

How, then, can a channel captain implement the optimal channel design, in the face of interdependence among channel partners, not all of whom have the incentive to cooperate in the performance of their designated channel flows? The answer lies in the possession and use of channel power. A channel member’s power “is its ability to control the decision variables in the marketing strategy of another member in a given channel at a different level of distribution.” These sources of channel power can of course be used to further one channel member’s individual ends. But if channel power is used instead to influence channel members to do t_ jobs that the optimal channel design specifies that they do, the result will be a channel that more closely delivers demanded service outputs, at a lower cost.

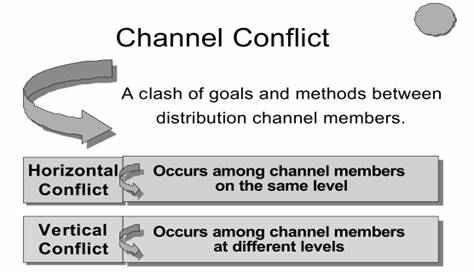

Channel Implementation: Identifying Channel Conflicts: Channel conflict is generated when one channel member’s actions prevent the channel from achieving its goals. Channel conflict is both common and dangerous to the success of distribution efforts. Given the interdependence of all channel members, anyone member’s actions have an influence on the total success of the channel effort, and thus can harm total channel performance

Channel conflict can stem from differences between channel members’ goals and objectives (goal conflict), from disagreements over the domain of action and responsibility in the channel (domain conflict), and from differences in perceptions of the marketplace (perceptual conflict). These conflicts directly cause a channel member to fail to perform the flows that the optimal channel design specifies for them, and thus inhibit total channel performance. The management problem is twofold. First, the channel manager needs to be able to identify the sources of channel conflict, and in particular, to differentiate between poor channel design and poor performance due to channel conflict. Second, the channel manager must decide on the action to take (if any) to manage and reduce the channel conflicts that have been identified.

In general, channel conflict reduction is accomplished through the application of one or more sources of channel power. For example, a manufacturer may identify a conflict in its independent-distributor channel: The distributorship is exerting too little sales effort on behalf of the manufacturer’s product line and therefore sales of the product are suffering. Analysis might reveal that the effort level is low because the distributorship makes more profit from selling a competitor’s product than from selling this manufacturers product. There is thus a goal conflict. The manufacturer’s goal is the maximization of profit over its own product line, but the distributorship’s goal is the maximization of profit over all of the products that it sells- only some of which come from this particular manufacturer. To resolve the goal conflict, the manufacturer might use one of the following strategies:

It might use some of its power to reward the distributor by increasing the distributor’s discount, thus increasing the profit margin it can make on the manufacturer’s product line. Or

the manufacturer may invest in developing brand equity and thus pull the product through the channel. In that case, its brand power induces the distributor to sell the product more aggressively because the sales potential for the product has risen.

In both cases, some sort of leverage or power on the part of the manufacturer is necessary to change the distributor’s behavior and thus reduce the channel conflict.

Channel Implementation: The Goal of Channel Coordination Now channel has been designed with target end-user segments’ service output demands in mind, and channel power will be appropriately applied to ensure the smooth implementation of the optimal channel design. When the disparate members of the channel are brought together to advance the goals of the channel rather than their own independent (and likely conflicting) goals, the channel is said to be coordinated. This term is used to denote both the coordination of interests and actions among the channel members who produce the outputs of the marketing channel, sand the coordination of performance of channel flows with the production of the service’ outputs demanded by target end-users. This is the end goal of the entire channel management process. As conditions change in the marketplace, the channel’s design and implementation may need to respond; thus, channel coordination is not a one-time achievement, but an ongoing process of analysis and response to the market, the competition, and the abilities of the members of the channel.