Now that we know that brand names are perceives by consumers as important informational clues, an explanation can be given by referring to the work by Miller. A research was carried out to understand the way the mind encodes information. For example, if we compare the mind with the way computers work, it can be seen that we can evaluate the quantity of information facing a consumer in terms of a number of ‘bits’. All the information on the packaging of a branded grocery item would represent in excess of a hundred bits of information. Researchers have shown that at most the mind can simultaneously process seven bits of information. Clearly, to cope with the information deluge from everyday life, our memories have had to develop methods for processing such large quantities of information.

The task facing the marketer is to facilitate the way we process information about brands, such that ever larger chunks can be built in the memory which, when fully formed, can then be rapidly accessed through associations from brand names. Frequent exposure to advertisements containing a few claims about the brand should help the chunking process through either passive or active information acquisition. What is really important, however, is to reinforce attributes with the brand name rather than continually repeating the brand name without at the same time associating the appropriate attributes with it.

The Challenge T o Branding From Perception

Brands and their reputations are valuable assets and a brand’s strategy needs regularly assessing to understand its suitability in changing environments. To overcome the problems of being bombarded by vast quantities of information and having finite mental capacities to process it all, we not only adopt efficient processing rules(for example, we use only high information value clues when choosing between brands, and aggregate small pieces of information into larger chunks) but we also rely upon our perceptual processes.

Perception is the process by which physical sensations such as sights, sounds, and smells are selected, organized, and interpreted. The eventual interpretation of the stimulus allows it to be assigned meaning. A consequence of this perceptual process is that consumers interpret brands in a different way from that intended by the marketer. The classic example of this was the cigarette brand Strand. Advertisements portrayed a man alone on a London bridge, on a misty evening, smoking Strand. The advertising slogan was ‘You’re never alone with a Strand’. Sales were poor, since consumers’ perceptual processes accepted only a small part of the information given and interpreted it as, ‘if you are a loner and nobody wants to know you, console yourself by smoking Strand’. It is clearly very important that brand marketers appreciate the role of perceptual processes when developing brand communication strategies.

Perception is information –processing activity

- Once stimuli become familiar they stop being sensed (habituation)

- Our sensory apparatus can screen out some information

- Selective attention to concentrate on some stimuli and ignore others

Perceptivity is based on

- Learning – (predisposition to pay attention/ignore)

- Personality – (extrovert/introvert effects on response to stimuli)

- Motivation – (response based on intrinsic motivators/ learned experiences)

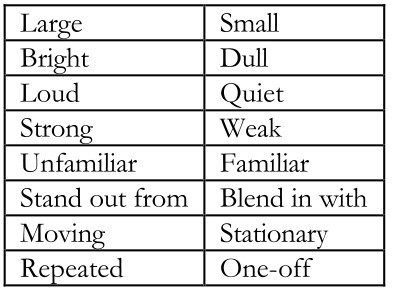

We concentrate on/rather than

Ways in which supermarket use perceptivity

- Different colours

- Placing goods (eye level/gondola ends)

- Depth of shelves

- Mirrors (especially fruit and vegetables)

- Curved shelving (eye follow-through

Perceptual Selectivity

The most important aspect of perceptual selectivity is attention. Everything else we perceive will be based on how much and what kind of attention we give to things around us. Attention is the process by which the mind chooses from among the various stimuli that strike the senses at any given moment, allowing only some to enter into consciousness.

Two main information-processing compartments –

- Automatic or pre-attentive processing- Unselective, Unlimited in capacity, Acting in parallel on all incoming information at once, Unconscious

- Controlled or attentive processing- Selective, Limited in capacity, Acts serially on a small portion of the available information, Partly conscious

Theories of Attention

Based on these components theories differ in their description of –

- The kind of processing that occurs pre-attentively (Stage 1).

- How the selector determines what passes into the second compartment.

- The kind of processing that occurs post-attentively (Stage 2).

Marketers invest considerable money and effort communicating with us, yet only a small fraction of the information is accepted and processed by us. First of all, their brand communication must overcome the barrier of what is known as Selective

Exposure

If a new advertisement is being shown on television, even though we are attentive to the programme during which the advertisement appears, when the commercial breaks are on, we may prefer to engage in some other activity rather than watching the advertisements. We either start surfing other channels or get up to have water, etc.

The second barrier is what is known as Selective Attention. We may not feel inclined to do anything else while the television commercials are on during our favorite programme and might watch the advertisement for entertainment, taking an interest in the creative aspects of the commercial. At this stage, selective attention filters information from advertisements, so building support for existing beliefs about the brand) Oh, it’s that Toyota advert. They are good reliable cars. Let’s see if they drive the car over very rough ground in this advert’) and avoiding contradicting claims(‘I didn’t realize this firm produces fax machines, besides the PC I bought from them, in view of the problems I had with my PC, I just don’t want to know about their products any more’)

The third challenge facing the brand is what is known as Selective Comprehension. We start to interpret the message and would that some of the information does not fit well with our earlier beliefs and attitudes. We then ‘twist’ the message until it became more closely aligned with our views. For example, after a confusing evaluation of different companies’ life insurance policies, a man may mention to his brother that he is seriously thinking of selecting a particular policy. When told by his brother that he knew of a different brand that had shown a better return last year, he may discount this fact, arguing to him that his brother as a Software engineer probably knew less about money matters than he did as a Sales Manager.

With the passage of time, memory becomes hazy about brand claims. Even at this stage, after brand advertising, a further challenge is faced by the brand. Some aspects of brand advertising are Selectively Retained in the memory, normally those claims which support existing beliefs and attitudes.

Thus, a consequence of perceptual selectivity, we are unlikely to be attentive to all the information transmitted by manufacturers or distributors. Furthermore, in instances where we consider two competing brands, the degree of dissimilarity may be very apparent to the marketer but if the difference, say, in price, quality or pack size is below a critical threshold this difference will not register with us. This is an example of what is known as Weber’s Law-the size of the least detectable change to the consumer is a function of the initial stimulus they encountered. Thus, to have an impact upon consumers’ awareness, a jewellery retailer would have to make significantly larger reduction on a Rs.2000 watch than on a Rs.100 watch

Activity

How many of you have seen the movie, Kal Ho Na Ho? Those of you who have seen tell me one thing that you liked best or worst about it. Remember just one best or worst thing! Now we see that our answers vary a lot, you may think why is it so?

This variety of reporting (observing?) is commonly obtained even though all the people are looking at the same scene. Why is there such diversity in what people say (and see)? At least part of the explanation is that people don’t just soak up the information that is in front of them. They look actively at the scene and report what they sought out and, to some extent, the sense that they were able to make of it.

Perceptual Organization

‘Perceptual organization’ allow us to decide between competing brands on the basis of their similarities within mental categories conceived earlier by us. We as consumers group a large number of competing brands into a few categories, since this reduces the complexity of interpretation. For example, rather than evaluating each car in the car market, we have mental categories such as Hyundai Santro as a small family car, Tata Safari as a sports utility vehicle and so on. By assessing which category the new brand is most similar to, we can rapidly group brands and are able to draw inferences without detailed search. If some of us place a brand such as Nanz’s own label washing powder into a category we have previously identified as ‘own label’, then the brand will achieve its meaning from its class it is assigned to by us. In this case, even we have little experience of the newly categorized brand, and then we use this perceptual process to predict certain characteristics of the new brand. For example, we may well reason that stores’ own labels are inexpensive, thus this own label should be inexpensive and should also be quite good.

Whilst it may be thought that the simplest way for us to form mental groups is to rely solely on one attribute and to categorize competing brands according to the extent to which they possess this attribute, evidence from various studies shows that this is often not the case. Instead, we use several attributes to form brand categories. Furthermore, it appears that we weight the attributes according to the degree of importance of each attribute. Thus, marketers need to find the few key attributes that are used by us to formulate different brand categorizations and major upon the relevant attributes to ensure that their brand is perceived in the desired manner.

Gestalt psychologists provide further support for the notion of consumers interpreting brands through ‘perceptual organization’. This school of thought argues that people see objects as ‘integrated wholes’ rather than a sum of individual’s parts. The analogy being drawn is that people recognize a tune, rather than listen to an individual collection of notes. The following are the principles of Gestalt study –

- Figure-ground – this is the fundamental way we organize visual perceptions. When we look at an object, we see that object (figure) and the background (ground) on which it sits. For example, when I see a picture of a friend, I see my friends face (figure) and the beautiful Sears brand backdrop behind my friend (ground).

- Simplicity/pragnanz (good form) – we group elements that make a good form. However, the idea of “good form” is a little vague and subjective. Most psychologists think good form is whatever is easiest or most simple. For example, what do you see here – – > ) do you see a smiling face? There are simply 3 elements from my keyboard next to each other, but it is “easy” to organize the elements into a shape that we are familiar with.

- Proximity – nearness=belongingness. Objects that are close to each other in physical space are often perceived as belonging together.

- Similarity – do I really need to explain this one? As you probably guessed this one state that objects that are similar are perceived as going together. For example, if I ask you to group the following objects – (* * # * # # #) into groups, you would probably place the asterisks and the pound signs into distinct groups.

- Continuity – we follow whatever direction we are led. Dots in a smooth curve appear to go together more than jagged angles. This principle really gets at just how lazy humans are when it comes to perception.

- Common fate – elements that move together tend to be grouped together. For example, when you see geese flying south for the winter, they often appear to be in a “V” shape.

- Closure – we tend to complete a form when it has gaps.