Is selling An Art or a Science?

Is selling a science with easily taught basic concepts or an art learned through experience? In a survey of 173 marketing executives, 46 percent perceived selling as an art, 8 percent as a science, and 46 percent as an art evolving into a science.9 The fact that selling is considered an art by some and a science by others has produced two contrasting approaches to the theory of selling.

The first approach distilled the experiences of successful salespeople and, to a lesser extent, advertising professionals. Many such persons, of course, succeeded because of their grasp of practical or learned-through-experience psychology and their ability to apply it in sales situations. It is not too surprising that these selling theories emphasize the “what to do” and “how to do” rather than the “why”. These theories, based on experiential knowledge accumulated from years of “living in the market” rather than on a systematic, fundamental body of knowledge, are subject to Howard’s dictum, “Experiential knowledge can be unreliable.”10

The second approach borrowed findings from the behavioral sciences. The late E.K. Strong, Jr. professor of psychology at the Stanford Graduate School of Business was a pioneer in this effort, and his “buying formula” theory is presented later in this section. John A. Howard of the Columbia Graduate School of Business was in the forefront of those who adapted the findings of behavioral science to analysis of buying behavior; his “behavioral equation,” discussed later in this section, attempts to develop a unified theory of buying and selling.

In this section we examine four theories. The first two, the “AIDAS” theory and the “right set of circumstances” theory, are seller oriented. The third, the “buying-formula” theory of selling, is buyer oriented. The fourth, the behavioral equation, emphasizes the buyer’s decision process but also takes the salesperson’s influence process into account.

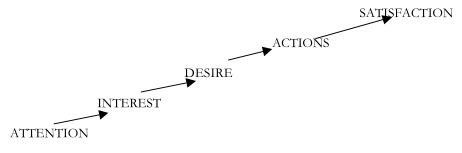

AIDAS Theory of Selling

This theory – popularly known as the AIDAS theory, after the initials of the five words used to express it (attention, interest, desire, action, and satisfaction) – is the basis for many sales and advertising texts and is the skeleton around which many sales training programs are organized. Some support for this theory is found in the psychological writings of William James, but there is little doubt that the construct is based upon experiential knowledge and, in fact, was in existence as early as 1898. During the successful selling interview, according to this theory, the prospect’s mind passes through five successive mental states: attention, interest, desire, action, and satisfaction. Implicit in this theory is the notion that the prospect goes through these five stages consciously, so the sales presentation must lead the prospect through them in the right sequence if a sale is to result.

Securing Attention

The goal is to put the prospect into a receptive state of mind. The first few minutes of the interview are crucial. The salesperson has to have a reason, or an excuse, for conducting the interview. If the salesperson previously has made an appointment, this phase presents no problem, but experienced sales personnel say that even with an appointment, as salesperson must possess considerable mental alertness, and be a skilled conversationalist, to survive the start of the interview. The prospect’s guard is naturally up, since he or she realizes that the caller is bent on selling something. The salesperson must establish good rapport at once. The salesperson needs an ample supply of “conversation openers”. Favorable first impressions are assured by, among other things, proper attire, neatness, friendliness, and a genuine smile. Skilled sales personnel often decide upon conversation openers just before the interview so that those chosen are as timely as possible. Generally it is advantageous if the openings remarks are about the prospect (people like to talk and hear about themselves) or if they are favorable comments about the prospect’s business. A good conversation opener causes the prospect to relax and sets the stage for the total presentation. Conversation openers that cannot be readily tied in with the remainder of the presentation should be avoided, for once the conversation starts to wander, and great skill is required to return to the main theme.

Gaining Interest

The second goal is to intensify the prospect’s attention so that it evolves into strong interest. Many techniques are used to gain interest. Some salespeople develop a contagious enthusiasm for the product or a sample. When the product is bulky or technical, sales portfolios, flipcharts, or other visual aids serve the same purpose.

Throughout the interest phase, the hope is to search out the selling appeal that is most likely to be effective. Sometimes, the prospect drops hints, which the salesperson then uses in selecting the best approach. To encourage hints by the prospect, some salesperson devise stratagems to elicit revealing questions. Others ask the prospect questions designed to clarify attitudes and feelings toward the product. The more experienced the salesperson, the more he or she has learned from interviews with similar prospects. But even experienced sales personnel do considerable probing, usually of the question and answer variety, before identifying the strongest appeal. In additional, prospects’ interests are affected by basic motivations, closeness of the interview subject to current problems, its timeliness, and their mood – receptive, skeptical, or hostile – and the salesperson must take all these into account in selecting the appeal to emphasize.

Kindling Desire: The third goal is to kindle the prospect’s desire to ready-to-buy point The salesperson must keep the conversation running along the main line toward the sale. The development of sales obstacles, the prospect’s objections, external interruptions, and digressive remarks can sidetrack the presentation during this phase. Obstacles must be faced and ways found to get around them. Objections need answering to the prospect’s satisfaction. Time is saved, and the chances of making a sale improved if objections are anticipated and answered before the prospect raises them. External interruptions cause breaks in the presentation, and when conversation resumes, good salespeople summarize what has been said earlier before continuing. Digressive remarks generally should be disposed of tactfully, with finesse, but sometimes distracting digression is best handled bluntly, for example, “Well, that’s all very interesting, but to get back to the subject

Inducing Actions: – If the presentation has been perfect, the prospect is ready to act- that is, to buy. However, buying is not automatic and, as a rule, must be induced. Experienced sales personnel rarely try for a close until they are positive that the prospect is fully convinced of the merits of the proposition. Thus, it is up to the salesperson to sense when the time is right. The trial close, the close on a minor point, and the trick close are used to test the prospect’s reactions. Some sales personnel never ask for a definite “yes” or “no” for fear of getting a “no”, from which they think there is no retreat. But it is better to ask for the order straightforwardly. Most prospects find it is easier to slide away from hints than from frank requests for an order.

Building Satisfaction: – After the customer has given the order, the salesperson should reassure the customer that the decision was correct. The customer should be left with the impression that the salesperson merely helped in deciding. Building satisfaction means thanking the customer for the order, and attending to such matters as making certain that the order is filled as written, and following up on promises made. The order is the climax of the selling situation, so the possibility of an anticlimax should be avoided – customers sometimes unsell themselves and the salesperson should not linger too long.

Stay Ahead with the Power of Upskilling - Invest in Yourself!

Stay Ahead with the Power of Upskilling - Invest in Yourself!