Restructurings have been occurring for hundreds of years. We will not go back that far to begin our overview of the market for corporate control. Synergy is ability of merged company to generate higher shareholders wealth than the standalone entities. Economically,

- it is the ability to further limit competitors’ ability to contest their or the targets’ current input markets, processes, or output markets,

- and/or it is the ability to open markets and/or encroach on their competitors’ markets where these competitors cannot respond.

Benefits of synergy in mergers and acquisitions

- Workforce efficiencies. Labour is the most expensive budget item in most businesses. In theory, consolidations make it possible to reduce the company’s workforce based on redundancies and other factors. But to deliver real results, the company needs to carefully restructure workflows to handle increased business volume.

- Combined technologies. An acquisition or merger typically results in the consolidation of the companies’ proprietary technologies and expertise. Acquisitions are frequently motivated by the desire to obtain a unique technology that is owned by a smaller business. True synergy only occurs when the consolidated technologies result in a strategic marketplace advantage.

- Scale efficiencies. Consolidation introduces the possibility of increased purchasing power and spending efficiencies that were previously beyond the reach of the individual companies. The new company can negotiate better terms based on its increased purchasing volume and weed out systemic inefficiencies rooted in duplications of services and/or capital assets.

- Market expansion. One of the most frequently cited synergistic advantages of an M&A scenario is increased market penetration. The combined efforts of the two companies will create a corporate powerhouse that will dominate the marketplace, easily displacing lesser brands and competitors.

Synergistic gains motivated many transactions during the era of friendly mergers. Synergy implies that the combination of firms itself creates value. Gains from synergy can arise from a variety of sources. Owning shares in a diversified company forced investors to own the company’s mix of industry exposure, which might not fit the risk preferences of all-or even most-investors. Gains from pure diversifying mergers were illusory at best.

If diversification does not explain mergers, why did so many smart executives spend time and money on these transactions? Very likely, the successful mergers and acquisitions of the 1960s relied on other sources of synergy to generate benefits. A few of the possible sources of gains include the following.

Increasing Market Power

Early mergers often saw companies in similar business lines join forces. Economists label such combinations horizontal mergers. Antitrust legislation prevents such combinations from resulting in monopolistic market power that creates the ability to raise prices indiscriminately. Nonetheless, larger firms may obtain some gains from their improved ability to negotiate with suppliers.

Growth for growth’s sake is never a sufficient reason for a merger or acquisition. Nonetheless, there have almost certainly been acquisitions completed solely for this reason. Managers have incentives to run larger companies. CEO compensation plans often relate salary to the size or growth rate of the company. The pride and prestige of managing a larger company may also affect some acquisition decisions. Managers who increase firm size to realize personal gains al-most always harm shareholders. When expansion increases shareholder wealth, those gains probably arise from economies of scope and scale, which we discuss next, rather than sheer size.

Economics of Scale

When companies merge, eliminating duplicated business functions can produce cost savings. If the total cost of per-forming a task increases more slowly than changes in volume, the production cost per unit falls. Economists call this condition decreasing average costs, or economies of scale. The costs of many business tasks, such as almost any computer-related task, behave this way.

Importance of economies of scale:

- Firstly, because a large business can pass on lower costs to customers through lower prices and increase its share of a market. This poses a threat to smaller businesses that can be “undercut” by the competition

- Secondly, a business could choose to maintain its current price for its product and accept higher profit margins.

Exploiting an Expertise (Economies of Scope)

Some mergers and acquisitions create value by exploiting economies of scope. Economies of scope arise when a company applies the same skill to a variety of products. For example, suppose that a company has a special skill in distributing items to drug-stores. Currently the company manufactures and distributes only vitamins and diet supplements.

The company might consider adding to the lines of goods it distributes to further exploit its distribution expertise. Adding product lines has very little effect on the company’s cost structure but increases its sales and profit potential. Thus, the firm might search for an acquisition candidate that would allow it to make fuller use of its distribution channels. Firms that can identify and exploit their special skills can earn profits that increase shareholders’ wealth.

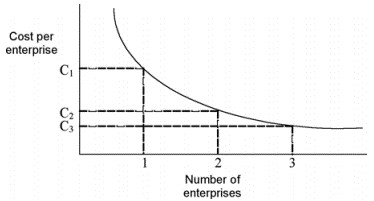

As shown in the figure below, the cost for an enterprise is cut in half if the resources are used in two enterprises rather than just one. If the use of the resources is spread over three enterprises, the cost per enterprise is reduced to a third.

Vertical Integration

Vertically integrated companies own several links in the entire production and sales chain. An example of vertical integration is an oil refining company that invests in oil reserves (the input to production) and gas stations (the retail distribution channel). Vertical integration assures a supply of inputs or outlets and can help protect a company’s proprietary information.

A value chain is as a set of discrete activities that must be accomplished to design, to build and to distribute a product or service. Each of these activities included in the value chain, must be accomplished in order to sell a product or service to customers. A firm may take different decisions over which activities to include in the value chain; the level of vertical integration defines the number of stages in a product’s or service’s value chain which a particular firm decides to engage in. The greater the number of stages in the value chain, the more vertically integrated a firm is. Whenever the firm increases the number of value chain stages it is engaged in, and these new stages bring it closer to direct interaction with the product’s or service’s ultimate customer, it is said to be in a forward vertical integration.

On the other hand, if the number of stages engaged in move farther away from the product’s or service’s ultimate customer, it is said to be a backward vertical integration.

Vertically integrated companies may lose the benefits of economies of scale. If the division that supplies a company’s inputs is not large enough to produce at the lowest cost volume, the cost of inputs produced internally may be higher than those purchased from optimally sized independent producers. The value of following a strategy of vertical integration depends on the frequency and cost of input shortages or the lack of outlets, and these benefits must be large enough to offset the various costs of integration.

According to the “resource dependence theory”, firms are assumed to pursue vertical integration strategies whenever the acquisition of a critical resource is uncertain and threatened. This theory can be understood as a particular example of governance choice a firm makes in managing its economic exchanges. Governance decisions are questions facing the most efficient way of managing (“governing”) a potentially valuable economic exchange. Usually a firm has a broad range of possible governance choices available, which goes from one extreme, called “market governance” to another extreme called “hierarchical governance”; midway there is the “intermediate governance”.