One of the basic principles of logistics costing, is that the system should mirror the materials flow, i.e. it should be capable of identifying the costs that result from providing customer service in the marketplace. A second principle is that it should be capable of enabling separate cost and revenue analyses to be made by customer type and by market segment or distribution channel. This latter requirement emerges because of the dangers inherent in dealing solely with averages, e.g. the average cost per delivery, since they can often conceal substantial variations either side of the mean.

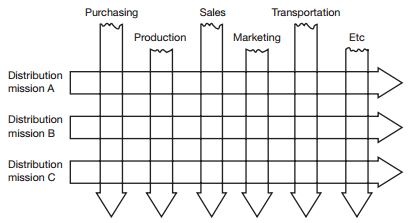

Figure : Logistics missions that cut across functional boundaries

First define the desired outputs of the logistics system and then seek to identify the costs associated with providing those outputs. In the context of logistics, a mission is a set of customer service goals to be achieved by the system within a specific product/market context. Missions can be defined in terms of the type of market served, by which products and within what constraints of service and cost. Figure above illustrates the concept and demonstrates the difference between an ‘output’ orientation based upon missions and the ‘input’ orientation based upon functions.

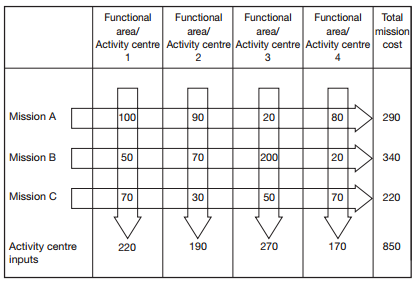

The successful achievement of defined mission goals involves inputs from a large number of functional areas and activity centres within the firm. Thus an effective logistics costing system must seek to determine the total systems cost of meeting desired logistic objectives (the ‘output’ of the system) and the costs of the various inputs involved in meeting these outputs.(also called ‘mission costing’)

Mission costing is the reverse of traditional techniques. This approach requires firstly that the activity centres associated with a particular distribution mission be identified, e.g. transport, warehousing, inventory, etc., and secondly that the incremental costs for each activity centre incurred as a result of undertaking that mission must be isolated. Incremental costs are used because it is important not to take into account ‘sunk’ costs or costs that would still be incurred even if the mission were abandoned. ‘Attributable costs’ can be used here. Attributable cost is a cost per unit that could be avoided if a product or function were discontinued entirely without changing the supporting organization structure.

Figure : The programme budget

In determining the costs of an activity centre, e.g. transport, attributable to a specific mission, the question should be asked: ‘What costs would we avoid if this customer/segment/channel were no longer serviced?’ These avoidable costs are the true incremental costs of servicing the customer/segment/channel. They might be lower than the average cost because so many distribution costs are fixed or shared. For example, a vehicle leaves a depot in Delhi to make deliveries in Chandigarh and Ambala.

If those customers in Ambala were abandoned, but those in Chandigarh retained, what would be the difference in the total cost of transport? The answer would be – not very much, since Chandigarh is further north from Delhi than Ambala. However, if the customers in Chandigarh were dropped, but not those in Ambala, there would be a greater saving of costs because of the reduction in miles traveled. This approach becomes particularly powerful when combined with a customer revenue analysis, because even customers with low sales off take may still be profitable in incremental costs terms if not on an average cost basis. In other words the company would be worse off if those customers were abandoned.

Such insights as this can be gained by extending the mission costing concept to produce profitability analyses for customers, market segments or distribution channels. The term ‘customer profitability accounting’ describes any attempt to relate the revenue produced by a customer, market segment or distribution channel to the costs of servicing that customer/segment/channel.

The cost of holding inventory

If all the costs that arise as a result of holding inventory are fully accounted for, then the real holding cost of inventory is probably in the region of 25 per cent per annum of the book value of the inventory. The largest cost element will normally be the cost of capital. The cost of capital comprises the cost to the company of debt and the cost of equity. It is usual to use the weighted cost of capital to reflect this. Hence, even though the cost of borrowed money might be low, the expectation of shareholders as to the return they are looking for from the equity investment could be high. The other costs that need to be included in the inventory holding cost are the costs of storage and handling, obsolescence, deterioration and pilferage, as well as insurance and all the administrative costs associated with the management of the inventory.

Stay Ahead with the Power of Upskilling - Invest in Yourself!

Stay Ahead with the Power of Upskilling - Invest in Yourself!