Logistics and the supply chain are concerned with physical and information flows and storage from raw material through to the final distribution of the finished product. Thus, supply and materials management represents the storage and flows into and through the production process, while distribution represents the storage and flows from the final production point through to the customer or end user.

The supply chain covers an even broader scope of the business area. This includes the supply of raw materials and components as well as the delivery of products to the final customer. Thus:

Supply Chain = Suppliers + Logistics + Customers

The term “supply chain management” entered the public domain when Keith Oliver, a consultant at Booz Allen Hamilton (now Booz & Company), used it in an interview for the Financial Times in 1982. The term was slow to take hold. It gained currency in the mid-1990s, when a flurry of articles and books came out on the subject. In the late 1990s it rose to prominence as a management buzzword, and operations managers began to use it in their titles with increasing regularity.

Typically, a supply chain is composed of two main business processes – material management (inbound logistics) and physical distribution (outbound logistics).

Material management is concerned with the acquisition and storage of raw materials, parts, and supplies. To elaborate, material management supports the complete cycle of material flow—from the purchase and internal control of production materials, to the planning and control of work-in-process, to the warehousing, shipping, and distribution of finished products.

On the other hand, physical distribution encompasses all outbound logistics activities related to providing customer service. These activities include order receipt and processing, inventory deployment, storage and handling, outbound transportation, consolidation, pricing, promotional support, returned product handling, and life-cycle support

Supply Chain Definitions

Commonly accepted definitions of supply chain management include:

- The management of upstream and downstream value-added flows of materials, final goods, and related information among suppliers, company, resellers, and final consumers.

- The systematic, strategic coordination of traditional business functions and tactics across all business functions within a particular company and across businesses within the supply chain, for the purposes of improving the long-term performance of the individual companies and the supply chain as a whole.

- A customer-focused definition is given by Hines ―Supply chain strategies require a total systems view of the links in the chain that work together efficiently to create customer satisfaction at the end point of delivery to the consumer. As a consequence, costs must be lowered throughout the chain by driving out unnecessary expenses, movements, and handling. The main focus is turned to efficiency and added value, or the end-user’s perception of value. Efficiency must be increased, and bottlenecks removed. The measurement of performance focuses on total system efficiency and the equitable monetary reward distribution to those within the supply chain. The supply chain system must be responsive to customer requirements.”

- The integration of key business processes across the supply chain for the purpose of creating value for customers and stakeholders.

- According to the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP), supply chain management encompasses the planning and management of all activities involved in sourcing, procurement, conversion, and logistics management. It also includes coordination and collaboration with channel partners, which may be suppliers, intermediaries, third-party service providers, or customers. Supply chain management integrates supply and demand management within and across companies. More recently, the loosely coupled, self-organizing network of businesses that cooperate to provide product and service offerings has been called the Extended Enterprise.

A supply chain, as opposed to supply chain management, is a set of organizations directly linked by one or more upstream and downstream flows of products, services, finances, or information from a source to a customer. Supply chain management is the management of such a chain. Supply chain management software includes tools or modules used to execute supply chain transactions, manage supplier relationships, and control associated business processes. Supply chain management software (SCMS) is a business term which refers to a whole range of software tools or modules used in executing supply chain transactions, managing supplier relationships and controlling associated business processes. While functionality in such systems can often be broad – it commonly includes:

- Customer requirement processing

- Purchase order processing

- Inventory management

- Goods receipt and Warehouse management

- Supplier Management/Sourcing

A requirement of many SCMS often includes forecasting. Such tools often attempt to balance the disparity between supply and demand by improving business processes and using algorithms and consumption analysis to better plan future needs. SCMS also often includes integration technology that allows organizations to trade electronically with supply chain partners. In 2012, the global supply chain management software market is estimated at $8.3 billion. The shift to global supply chain networks shifted supply chain systems to cloud-based technology. This encouraged technology that have all partners on the same software version, a single source of truth for all software, and the implementation of software technology with pay for what you use software supply chain event management (SCEM) considers all possible events and factors that can disrupt a supply chain. With SCEM, possible scenarios can be created and solutions devised. In many cases the supply chain includes the collection of goods after consumer use for recycling. Including third-party logistics or other gathering agencies as part of the RM repatriation process is a way of illustrating the new endgame strategy.

Problems Addressed

Supply chain management addresses the following problems:

Distribution network configuration: the number, location, and network missions of suppliers, production facilities, distribution centers, warehouses, cross-docks, and customers.

Distribution strategy: questions of operating control (e.g., centralized, decentralized, or shared); delivery scheme (e.g., direct shipment, pool point shipping, cross docking, direct store delivery, or closed loop shipping); mode of transportation (e.g., motor carrier, including truckload, less than truckload (LTL), parcel, railroad, intermodal transport, including trailer on flatcar (TOFC) and container on flatcar (COFC), ocean freight, airfreight); replenishment strategy (e.g., pull, push, or hybrid); and transportation control (e.g., owner operated, private carrier, common carrier, contract carrier, or third-party logistics (3PL)).

Trade-offs in logistical activities: The above activities must be coordinated in order to achieve the lowest total logistics cost. Trade-offs may increase the total cost if only one of the activities is optimized. For example, full truckload (FTL) rates are more economical on a cost-per-pallet basis than are LTL shipments. If, however, a full truckload of a product is ordered to reduce transportation costs, there will be an increase in inventory holding costs, which may increase total logistics costs. The planning of logistical activities therefore takes a systems approach. These trade-offs are key to developing the most efficient and effective logistics and SCM strategy.

Information: The integration of processes through the supply chain in order to share valuable information, including demand signals, forecasts, inventory, transportation, and potential collaboration.

Inventory management: Management of the quantity and location of inventory, including raw materials, work in process (WIP), and finished goods.

Cash flow: Arranging the payment terms and methodologies for exchanging funds across entities within the supply chain.

Supply chain execution means managing and coordinating the movement of materials, information and funds across the supply chain. The flow is bi-directional. SCM applications provide real-time analytical systems that manage the flow of products and information throughout the supply chain network.

Functions of Supply Chain Management:

Supply chain management is a cross-functional approach that includes managing the movement of raw materials into an organization, certain aspects of the internal processing of materials into finished goods, and the movement of finished goods out of the organization and toward the end consumer. As organizations strive to focus on core competencies and becoming more flexible, they reduce their ownership of raw materials sources and distribution channels. These functions are increasingly being outsourced to other firms that can perform the activities better or more cost effectively. The effect is to increase the number of organizations involved in satisfying customer demand, while reducing managerial control of daily logistics operations. Less control and more supply chain partners led to the creation of the concept of supply chain management. The purpose of supply chain management is to improve trust and collaboration among supply chain partners, thus improving inventory visibility and the velocity of inventory movement.

Importance of Supply Chain Management

Organizations increasingly find that they must rely on effective supply chains, or networks, to compete in the global market and networked economy. In Peter Drucker’s (1998) new management paradigms, this concept of business relationships extends beyond traditional enterprise boundaries and seeks to organize entire business processes throughout a value chain of multiple companies. In recent decades, globalization, outsourcing, and information technology have enabled many organizations, such as Dell and Hewlett Packard, to successfully operate collaborative supply networks in which each specialized business partner focuses on only a few key strategic activities (Scott, 1993). This inter-organisational supply network can be acknowledged as a new form of organisation. However, with the complicated interactions among the players, the network structure fits neither “market” nor “hierarchy” categories (Powell, 1990). It is not clear what kind of performance impacts different supply network structures could have on firms, and little is known about the coordination conditions and trade-offs that may exist among the players. From a systems perspective, a complex network structure can be decomposed into individual component firms (Zhang and Dilts, 2004). Traditionally, companies in a supply network concentrate on the inputs and outputs of the processes, with little concern for the internal management working of other individual players. Therefore, the choice of an internal management control structure is known to impact local firm performance (Mintzberg, 1979). In the 21st century, changes in the business environment have contributed to the development of supply chain networks. First, as an outcome of globalization and the proliferation of multinational companies, joint ventures, strategic alliances, and business partnerships, significant success factors were identified, complementing the earlier “just-in-time”, lean manufacturing, and agile manufacturing practices. Second, technological changes, particularly the dramatic fall in communication costs (a significant component of transaction costs), have led to changes in coordination among the members of the supply chain network (Coase, 1998). Many researchers have recognized supply network structures as a new organisational form, using terms such as “Keiretsu”, “Extended Enterprise”, “Virtual Corporation”, “Global Production Network”, and “Next Generation Manufacturing System”. A keiretsu (system, series, grouping of enterprises, order of succession) is a set of companies with interlocking business relationships and shareholdings. It is a type of informal business group. The keiretsu maintained dominance over the Japanese economy for the last half of the 20th century. The member companies own small portions of the shares in each other’s companies, centered on a core bank; this system helps insulate each company from stock market fluctuations and takeover attempts, thus enabling long-term planning in innovative projects. It is a key element of the automotive industry in Japan. In general, such a structure can be defined as “a group of semi-independent organisations, each with their capabilities, which collaborate in ever-changing constellations to serve one or more markets in order to achieve some business goal specific to that collaboration”.

The security management system for supply chains is described in ISO/IEC 28000 and ISO/IEC

28001 and related standards published jointly by the ISO and the IEC. Supply Chain Management draws heavily from the areas of operations management, logistics, procurement, and information technology, and strives for an integrated approach.

Benefits of SCM

Various benefits of SCM and its integration in a company are

- Improved customer service and value added—Customer service can be improved through increased inventory availability, better on-time delivery performances, higher order fill rates, and lower post-sales costs.

- Enhanced fixed capital—Fixed capacity is maximized through a strategic partnership and joint planning that can increase overall capacity and throughput.

- Utilized asset—Asset utilization can be maximized by increasing inventory turns and closely aligning supply with demand.

- Increased sales and profitability—The ability to assess outcomes due to price changes, promotional events, and new product development can be enhanced through increased visibility resultant from information sharing among supply chain partners.

Total Systems View

A traditional business paradigm intends to react to unforeseen customer demand on a “push” basis by building buffers such as inventory that mitigate forecasting errors and hide distribution/production planning problems.

The traditional business paradigm is also characterized by the sequential flow of information from one business function to another. Because the sequential information flow does not give an organization the opportunity to synchronize its functional activities and will impair its visibility throughout the planning processes, the same hidden problems will recur and the vicious cycle of inefficiency will continue without the problems ever being addressed. The best way to break this vicious cycle is to create a system that allows the organization to see the big picture of the business processes and then analyze the impact of the whole business processes on the organizational-wide goals rather than the departmental/ functional goals. In other words, to continuously improve business processes, the traditional business paradigm should be replaced by the total system approach, which can create a whole greater than the sum of its parts. Therefore, the total systems approach is considered a major foundation for the supply chain concept.

The total systems approach regards the supply chain as an entity that is composed of interdependent or interrelated subsystems, each with its own provincial goals, but which integrates the activities of each segment so as to optimize the system-wide strategic objectives.

As the extended enterprise perspective brought by the total systems approach has become the important foundation of supply chain thinking, we have witnessed increasing boundary-spanning activities across the supply chain. Typically, these boundary-spanning activities have played three different roles

- Gatekeeping—They single out potential suppliers and third-party logistics providers through a request for proposal (RFP) and then help the firm to make an informed decision as to who will be selected as the supply chain partner among a managerial list of candidates.

- Transacting—They develop all aspects of business trading opportunities with the potential supply chain partners on an equal footing.

- Protecting—They ensure conformance with contract terms and conditions, delivery schedules, product/service quality, and other partnership agreements.

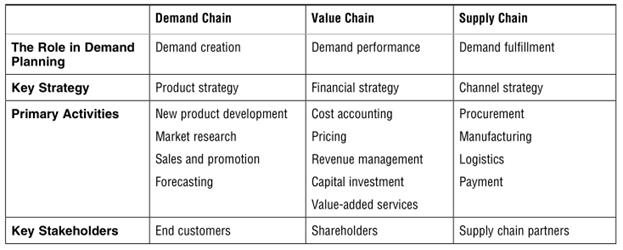

Demand, Value and Supply Chain

The ultimate goal of supply chain management is to serve the customer better, supply chain management begins with the understanding of customer values and requirements. Indeed, Poirier argued that the primary objective of supply chain improvements was to serve ultimate customers more effectively and therefore an analysis of the supply chain should focus on the “finish line” (demand), not the “starting point” (supply). To enhance the customer values and meet customer requirement, careful planning of demand-creation and -fulfillment activities is critical to the success of the whole organization. This planning cannot be articulated without understanding the dynamics of interrelated business activities and jointly developing ideas for business process improvement among the intra- and inter-organizational units. Therefore, any efforts geared toward the customer-centric and “pull” approach throughout the entire business processes are considered part of the demand chain.

In a context similar to the demand chain, a value chain is referred to as a series of interrelated business processes that create and add value for customers. Its intent is to disaggregate all of a firm’s business processes into discrete activities to evaluate their level of contributions to the firm’s value and then discern value-adding activities from non-value-adding activities. Herein, “value is the amount buyers are willing to pay for what a firm provides them and thus is measured by total revenue, a reflection of the price a firm’s product commands and the units it can sell”. Thus, the extent of value created and added by the firm often dictates its level of business success, because the higher the value, the greater the profit margin and competitive advantages.